Ottoman Dreams, Syrian Nightmares, and the Triangle Wars, Part 1

“The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers...”

This note was sent to my institutional clients on 28 March, 2021. With Turkey eyeing up northern Syria again and Iran warning them off, the topic will be front page again soon. Comments are open to all on this one. What do you think Erdogan’s plans are for northern Syria and the Eastern Med?

· Erdoğan’s actions must be viewed in the context of a man who needs a reliable supply of dollars. Providing a massive dollar swap line would do a lot to calm Erdoğan’s foreign policy adventures.

· The past ten years have been a series of contests across the Middle East for control over identities in pursuit of legitimization of power. The economic crisis in Turkey is bringing to a head an ongoing contest of identities and forcing Erdoğan to reconcile conflicts within his ruling coalition.

· Being an energy transit country or, even better, an energy hub, would solve Turkey’s dollar deficit problems and give a major boost to its diplomatic power.

A changeover of the US presidency, COVID, and the Fed have kept investor attention away from the Middle East recently. In addition to the distractions, Trump’s loss prompted the region’s more “eccentric” leaders to tread more carefully. The brief period of calm is coming to an end as the currency crisis in Turkey looks increasingly likely to force Erdoğan’s hand. Adventures in foreign conquest are always fraught with danger, even under the best of circumstances, but when desperation enters the mix the situation becomes explosive.

Numerous overlapping conflicts rage – ideological, political, commercial – from the tropical shores of Guinea-Bissau to the bone-dry mountains of Xinjiang. These conflicts, although not directly connected, all revolve around control over the energy resources and transportation corridors of the Middle East and Central Asia. The areas of interest form two triangles that meet in the eastern Mediterranean (“EastMed”) (Map A). Conflict over these transportation routes, recently intensified by China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative (“BRI”), is not a new phenomenon (Map B). Indeed, a good indicator of who runs the Middle East is who controls Syria[1]. This note is the first in a series examining the geopolitical situation across the two triangles beginning with Turkey, where the clock is currently ticking fastest.

Ottoman Dreams, Turkish Realities

The past ten years have been a series of contests across the Middle East for control over identities in pursuit of legitimization of power[1]. In past notes I have discussed the conflict of identities playing out in Saudi Arabia[2], Iraq[3], and Sudan[4]. The current economic crisis in Turkey is bringing to a head an ongoing contest of identities and, as a result, forcing Erdoğan to reconcile conflicts within his ruling coalition. As long as his political machine could be greased with graft, Erdoğan could keep the Islamists of AKP and Turkic Nationalists of MHP happy under one tent. However, tough economic conditions require tough choices, and the Islamists and nationalists are looking to Erdoğan for ideological commitment. This is a political tin can Erdoğan has kicked down the road since AKP lost its outright majority in 2015.

Erdoğan has been a lifetime supporter of political Islam, even going to prison for it, and romanticizes a Golden Age when Istanbul was considered the center of the Islamic world. The city rests on historic foundations much deeper than the Ottomans and Erdoğan’s recent actions show he is well-aware of its symbolic importance. There was a time when Constantinople was the seat of power for the Byzantine-Roman Empire and represented the Christian version of Rome’s grandeur and centrism. Indeed, when Mehmed the Conqueror took Constantinople in 1453AD, he crowned himself Emperor of Rome and saw his rule as an unbroken continuation of the empire. Erdoğan makes no secret about Mehmed being his personal hero and he honored the Sultan by turning the Hagia Sophia “museum” back into a mosque.

Erdoğan wants to be the Sultan of an ideological-commercial Neo-Ottoman Empire, a “soft” empire. However, he must operate in the context of a country steeped in strict secularist nationalism from its founding in 1923 until 2002, when AKP came to power. Erdoğan’s political brand depends on maintaining a delicate balance between pious Islamism and bellicose nationalism, so he has created a syncretism of pan-Turkism and neo-Ottomanism. Erdogan leans his political boat towards nationalism or Islamism as the winds favor.

Erdoğan’s political machinations operate within an economy hobbled by corruption and chained to foreign energy imports (Charts 1 and 2). Of course, Erdoğan and his associates built the corruption machine currently in place and they depend on it for their political power and personal enrichment – so that path is off the table. The problem that Erdoğan can address is Turkey’s persistent current account deficit, which is driven by a lack of domestic energy resources. Turkey, as it always has, sits as the gatekeeper between the natural resources of Asia and the markets of Europe. Erdoğan wants to secure Turkey’s position, and his own, as a world power, by securing one or both energy triangles discussed above.

Erdogan’s Hill of Sand

Strong economic growth, geopolitical clout, and political Islam are the pillars of AKP’s political power. The weakest of the three has always been political Islam, due to Turkey’s secular militarist history. When AKP was able to deliver economic growth and national progress the business community and Turkish nationalists were happy to indulge Erdoğan’s Islamist tendencies. Growth was strong after AKP came to power but was interrupted by the global recession of 2008-2009 (Chart 3). At the time Erdoğan could, and did, blame “the West” for Turkey’s economic problems. However, the deterioration of economic conditions in Turkey since 2018 have been a political disaster for Erdoğan because he is running out of others to blame (Chart 4). A very real possibility is that the blame will fall on the 2.5 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey, who the main opposition party (CHP) wants to deport back to Syria.

Turkey’s recovery after the Great Recession was driven by investments in infrastructure and luxury real estate, culminating in a residential property price bubble (Chart 5). Government-directed infrastructure investment included a doubling of electric generation capacity between 2010 and 2020. To put that “achievement” in perspective, during that decade electricity consumption only rose by 44%, leaving substantial overcapacity sitting idle. Further distortion of the economy is in the pipeline as another twenty-five percent increase in generation capacity is under construction.

Qatari money has flowed into the country since 2015 as the diplomatic and security relationships between the two countries grew stronger. The Qataris have made significant investments in BMC, maker armored personnel carriers. BMC is a joint venture between Qatar’s armed forces and a businessman loyal to Erdogan. Qatar has also spent heavily on luxury real estate developments in Turkey, but its most important contribution has been a $15 billion swap facility with Turkey’s central bank.

The consequence of all this politically determined investment is a major overhang of low-return capital, leaving the economy vulnerable to rising real interest rates. When the central bank hiked interest rates in 2018 to defend the lira, gross fixed capital formation suffered a collapse greater than that during the Great Recession. The 2018 crisis was also worse for Turkey than the Great Recession as measured by private consumption. Indeed, the only sector of the economy that has continued to grow at its pre-2018 trend is the government (Chart 6).

Erdoğan’s domestic status as an economic rainmaker has been AKP’s claim to power since winning the 2002 elections. But once Turkey’s current account deficit is considered, any claims of economic success become dubious (Chart 7). Turkey’s investment boom after 2002 - and the associated, seemingly, unbound growth possibilities – were only possible because foreign investors provided capital. In 2014, global investors began reconsidering Turkey’s risk profile and credit spreads began to widen. Turkey’s status as an emerging market was confirmed once the lira began weakening in step with rising credit spreads (Chart 8). Lira carry a liquidity risk driven by credit assessment, preventing the currency from adjusting purely due to fundamentals.

In 2017, international financial markets put their foot down. Turkish bond spreads rose considerably, and non-financial international debt peaked. The dollar market had taken the punch bowl away from Turkey and, lacking another means of obtaining cheap dollars, the party was over (Chart 9). The good news is that Turkey’s dollar liabilities are well spread across different maturities and different sectors of the economy - the issue is not by any means one of imminent economic collapse (Chart 10). A better description of Turkey’s condition would be long-term unsustainability with extreme short-term political risk.

The Funding Gap

Credit and FX markets are appropriately concerned about Turkish governance. Turkish debt levels, including external debt, are not alarmingly high. However, Turkey has a substantial ongoing need for dollars to service debt and fund energy imports (Chart 11). The Turkish government is unable to provide either cheap and stable energy prices, or cheap and easy dollar funding - international markets are reacting.

The situation became critical after the 2016 coup attempt. Despite lower oil prices, higher debt service payments drastically increased the flow of dollars Turkey needs to stay solvent. The supply of reserves as a percentage of external debt had been falling since 2012 but became critical in in 2018 and the lira took a beating (Chart 12). The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) drastically increased its policy rate to defend the lira and the private sector’s cost of servicing its debt jumped (Charts 13 and 14). This is what Erdoğan means when he says that high interest rates cause inflation.

Turkey’s government balance sheet is not where the national leverage is hidden. Rather, it is in government guarantees of business debt, see below for more on this. As a result, when policy rates rise businesses face rising financing costs on foreign and domestic loans until the lira recovers. The government uses businesses as a quasi-fiscal tool by providing government guarantees to firms that are “government friendly”. When financing costs for these firms rise, Erdogan’s primary policy tool is stuck in reverse.

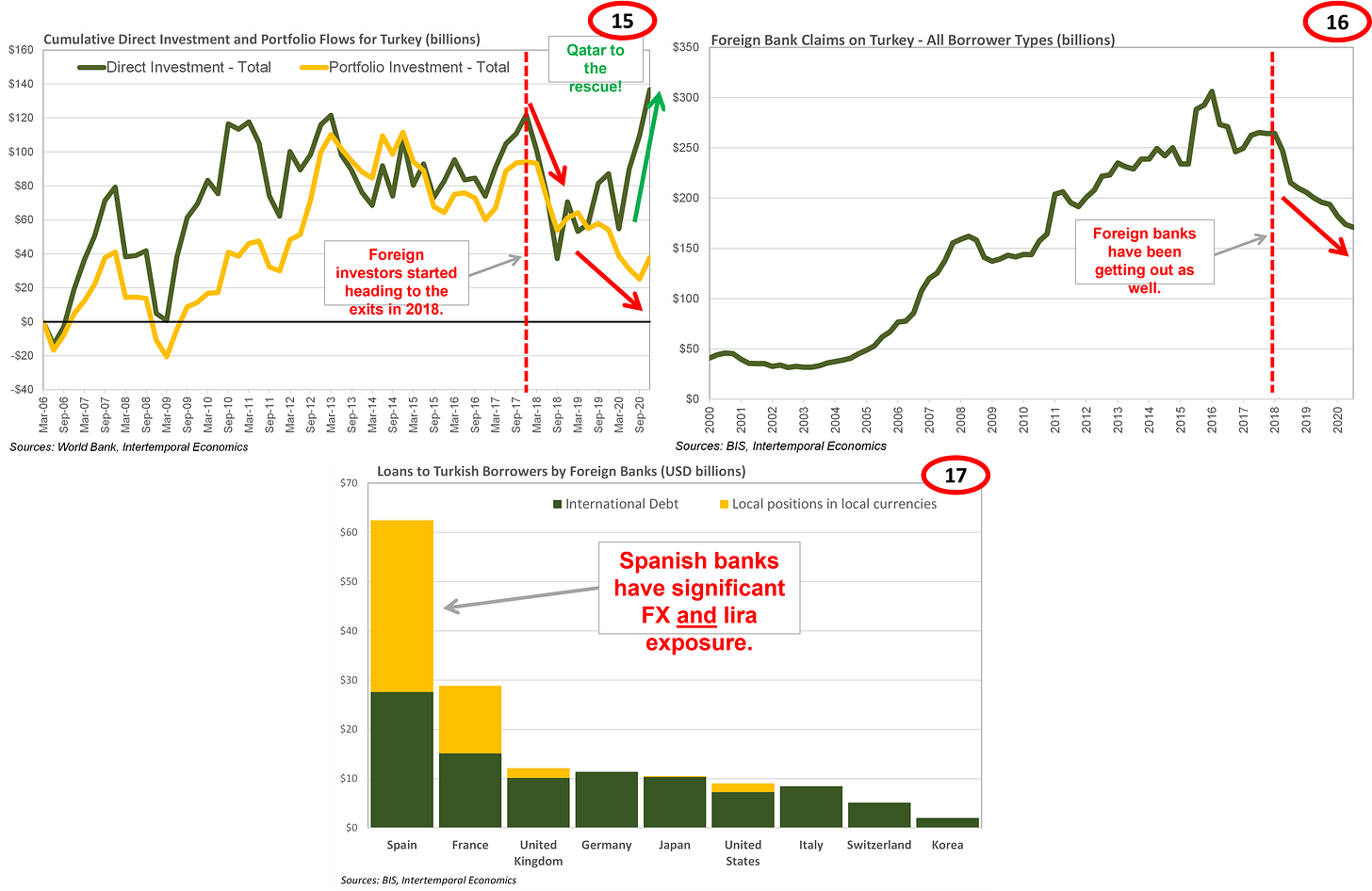

Foreign investors enthusiastically funded Turkey’s current account deficit before the Great Recession and continued to do so, albeit more cautiously, after the global recession. However, the currency crisis of 2018 was a signal for foreign investors to start heading for the exits. Portfolio investors and firms making direct investments began pulling out money as soon as the currency crisis started (Chart 15). Direct investment jumped in 2020 when Qatar rode to Turkey’s rescue with real estate investments. Foreign banks have also been pulling back from Turkish borrowers (Chart 16). Once Turkey’s difficulty getting its hands on hard currency became clear, nobody wanted to be the one holding a bag of lira assets. Spanish banks have been the slowest to react and retain significant exposure to Turkey (Chart 17).

Turkey’s government has responded to the dollar deficit problem with short-term solutions that have made the problem worse over time. In February 2020, before COVID hit the scene, the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency limited foreign exchange transactions to ten percent of a bank’s equity. This was the second tightening of foreign exchange regulations after the limit was reduced from fifty percent to twenty-five percent in August 2018. This policy, along with others designed to cling to scare dollars have had the unintended effect of scaring away foreign investors.

COVID Consequences

Fiscal limitations dictated the Turkish government’s response to the COVID crisis. The government avoided shut-down orders as much as possible and direct cash payments amounted to less than one percent of GDP. The central bank cut interest rates aggressively and government programs shoveled loans out the door of state-owned banks (Chart 18). A housing and vehicle boom took place in late 2020 but has since petered out (Chart 19). The government had already been handing out loans on easy terms to small businesses, a key Erdoğan constituency. The massive credit expansion that took place in 2020 had the predictable effect of depressing non-performing loan rates (Chart 20). The beneficial effects were barely felt in the construction industry, which was already in shambles, giving a taste of the structural problems that remain (Chart 21).

Conclusion

Turkey’s geopolitical situation is very interesting because the country has a great location but almost no domestic energy resources. Erdoğan’s actions must be viewed in the context of a man who needs a reliable supply of dollars. Of course, one way to economize on dollars is to reduce the national cost of energy. However, being a transit country or, even better, an energy hub, also provides a steady stream of dollars skimmed off the flow between buyers and sellers of energy. Erdoğan’s original political brand of Islamism drew his attention south, to the former territories of the Ottoman Empire. However, it has proved difficult for Turkey to secure supplies and a transit route from the Middle East and Africa. That led Erdoğan to change his brand to being a pan-Turkic nationalist in order to pivot to the northern triangle that stretches across the energy resources of Central Asia.

Erdoğan’s aggressive, sometimes desperate, foreign policy moves should always be understood as furthering his personal position. To regain the confidence of international investors Turkey needs a steady stream of dollars to service international debt with. With a return of foreign capital will come the ability to fuel a credit bubble without crushing the lira and driving inflation. Providing a “no questions asked” dollar swap line to Turkey would do a lot to calm down Erdoğan’s foreign policy adventures. In my next note I will explore the role of a natural gas hub, Turkey’s likelihood of meeting the necessary requirements, and the fruits of Erdogan’s efforts.

1] See my Connolly Insight note “Obama, Putin, and the Coalition of the Twelfth Imam” of 9 October 2015.

[1] See my note “The King, The Sultan, and The Caliphate” of 24 February 2019.

[2] See my Connolly Insight note “Saudi Arabia: Sunni or Arab?” of 23 December 2015.

[3] See my notes “Cutting up What Remains”, Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of 14 November 2019, 2 December 2019, and 14 January 2020.

[4] See my note “The Red Sea, The White Nile, and the Blue Peoples” of 20 July 2019.

That 'skimming' you write off, we even have a word for that now in our neck of the woods: "huachicoleo." Risky business.