Ottoman Dreams, Syrian Nightmares, and the Triangle Wars, Part 2

Erdogan's quest to turn shackles made for Turkey into a leash for Europe.

This note was distributed to institutional clients on 7 April 2021. The political and economic stability of Turkey continues to deteriorate and coming months will be critical ones for the region. Do you think Erdogan will succeed in his goal of muscling into the Eastern Mediterranean? Could Turkey serve at a regional gas hub? Comments are open to all so please sound off!

· Hosting a major hub brings with it not only prestige and supply security, but also easy access to a constant flow of dollars going through the banking system as a byproduct of contract settlement. Having an “offshore” hub would give Turkey the best of both worlds.

· Erdoğan’s efforts to turn Turkey into a gas hub has already produced fruit in Europe. In December 2020, the EU applied weak sanctions against Turkey for its actions in the eastern Mediterranean.

· For the time being, Turkey remains a mere transit country, neither a producer nor the host of a hub. As a result, Erdoğan has resorted to harder tactics to gain access to gas supplies in Central Asia and/or the eastern Mediterranean – the two triangles discussed in Part 1.

Turkey’s Dollar Deficit

In Part 1 of this note I discussed Turkey’s dollar deficit problem and the political problems it has caused for Erdoğan. Turkey’s need to import nearly its entire energy supply drives a constant need for dollars, but the country has no corresponding source of dollars (Chart 1). The mismatch limits Turkey’s ability to borrow internationally, making the economy highly dependent on foreign direct investment (Chart 2). Erdogan needs dollars to plug an international funding hole, which would allow further leverage and ensure his reelection.

As a transit country, Turkey can collect a small tariff from pipeline owners. But, as seen with Ukraine, transit tariffs hardly cover the bill for domestic natural gas use[1]. More importantly, transit countries remain hostage to pipeline owners, even if multiple suppliers are available. If Russia cuts off Turkey’s gas supply the latter cannot simply tap the pipelines - the gas in them is contracted for someone else bilaterally with Russia. This note explores Erdoğan’s options for turning energy from a shackle made for Turkey into a leash made for Europe.

The Pipes that Bind

In 2019, about 20% of Turkey’s electricity demand was met with natural gas, down significantly after hydroelectric capacity expanded in 2018 (Chart 3). Turkey has a reserve margin of power generation, but a total cut-off of Russian gas could cause a shut down of the electric grid. In the longer-term, any attempt at EU membership by Turkey will require a substantial reduction of carbon-dioxide output. The only economically viable method is to replace coal with natural gas in electricity generation.

The demand for natural gas by the manufacturing and residential sectors in Turkey is substantial (Chart 4). Indeed, eighty percent of households in Turkey are served with natural gas and most use the fuel for heat as well as cooking. A shortage of gas during a cold snap could force Turkish authorities to decide between heat and power. No matter how you look at it, the Turkish economy needs a cheap and reliable supply of natural gas to be viable in its current form.

Energy consumers around the world have benefited from the massive increase in global natural gas supply, but the benefit has been slow to be felt in Turkey. Historically, contracts for pipeline gas lasted for decades and were tied to the price of oil. Deals signed by BOTAS, Turkey’s state-owned gas provider, in the 1980s and 1990s are only now coming to an end (Chart 5).

The deals for Russian pipeline gas are set based on the price of oil and are much slower to adjust than the spot market for LNG (Chart 6). Global LNG trade has been transformative because it enabled a global spot market that reflects the global supply of natural gas. Turkey needs to break away from bilateral contracts - where the gas supplier has the advantage – and move to the spot market. Given the rising supply of LNG available, buyers are at an advantage in the spot market. Of course, making a break from Russian contracts to a spot market has been a goal of the U.S., EU, and Turkey for decades. But none have succeeded.

The Southern Corridor

After the Russo-Ukraine gas crisis of 2006, the European Commission launched a double strategy. First, encourage energy flows between EU countries. Second, diversify natural gas supplies by encouraging LNG imports and creation of a “Southern Gas Corridor”. The EC’s statement on the issue in 2008 said that the SGC was one of the highest energy security priorities for the EU and that the project requires working with Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Iraq. A prior project, Nabucco, had been agreed upon in 2002 that would have gathered gas from across central Asia and the Middle East including: Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Iraq, Iran, and Egypt. The vision was a natural gas version of the Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline that reduced the EU’s dependence on Russian oil in the 1990s. However, the Nabucco project failed to get off the ground amidst multi-lateral negotiations and the uncertainty of profitability created by Russia’s proposal of a “South Stream” pipeline – as intended by the Russians. In the end, neither project was completed (Maps A and B).

The grand vision for a multilateral project with multiple buyers and sellers fell apart because of the complexity but a smaller project involving only two parties was able to happen. Azerbaijan changed the game in 2011 when it unveiled its own pipeline, the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), which had the benefit of being a bilateral deal between Turkey and Azerbaijan. With its oil revenues Baku was able to self-finance the project. After TANAP, self-funded national pipelines by non-Russian producers were on the table.

Opening the route to Europe for producers other than Russia was a good start but the situation is still one of fragmented markets dominated by non-transparent bilateral agreements. A more permanent solution would require de-nationalizing the gas supplies and creating a liquid market, which would prevent national priorities from getting in the way of doing business. De-nationalization requires a physical hub where gas becomes fungible as it enters a wider distribution network.

The Hub as a Solution

A gas trading hub is a platform where enough buyers and sellers are available such that they can trade at fair prices at short notice in a reliable environment. The situation is optimal because price formation is transparent and at arm’s length, rather than secretive and tied to international relations. Gas hubs fall into two categories – virtual and physical. Virtual hubs assume the gas distribution network has a single point where gas is traded, in Europe the biggest virtual hubs are NBP (UK) and TTF (Netherlands). Physical gas hubs require vast storage facilities and connections to a network of buyers and sellers. A physical hub can serve as a point of delivery for futures contracts and, when combined with LNG facilities to provide a connection to the global market, a stable and transparent market price can form. Usually, non-commercial traders (i.e. speculators) are needed because there are not enough natural buyers and sellers available to provide continuous liquidity. For international speculative traders to be comfortable, corruption and political coercion need to be kept to acceptable levels, and a stable financial system must be available.

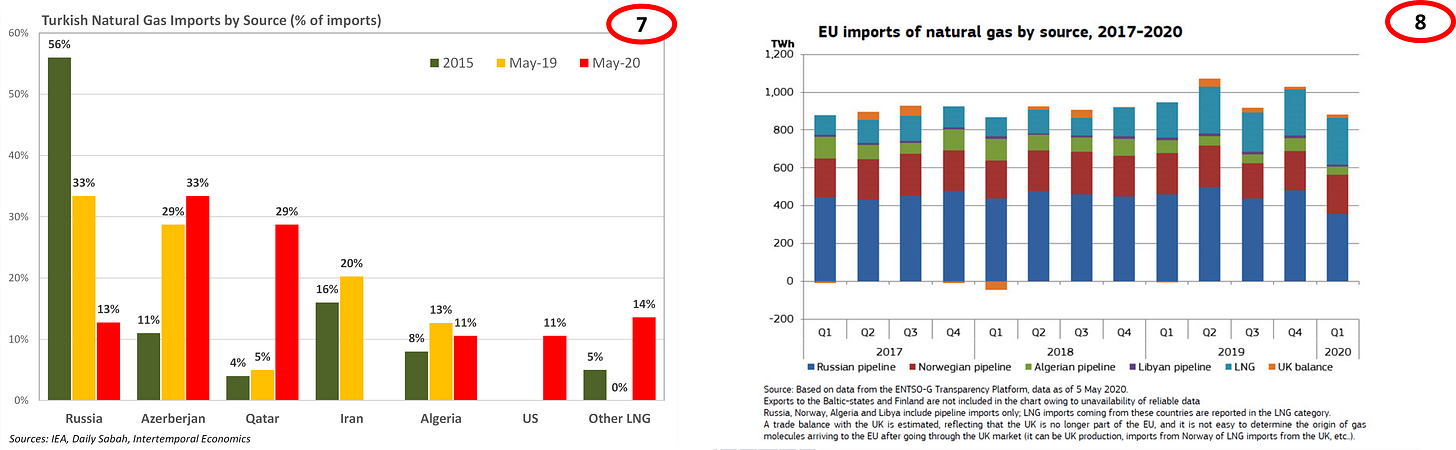

The EU (read Western Europe) is desperate to reduce the market power that Russia holds, even if Russia’s market share remains constant or rises. De-nationalizing gas at a hub outside of the EU would allow Russia to sell gas to Europe without EU compliance. It would also – in theory – limit Russia’s ability to use gas supply as a threat. Since 2015, Turkey has been successful in reducing its reliance on Russia for pipeline gas and increasing the number of sources of LNG supply (Chart 7). The EU, by contrast, has remained heavily reliant on Russian pipeline gas (Chart 8). There are a limited number of locations that can serve as physical hubs. With North Sea production fading, only Turkey has geographic access to a wide variety of producers via pipeline and LNG imports. The physical infrastructure is in-place and the geographic location is convenient, but Turkey lacks several key requirements for being a successful gas hub.

Turkey as a Gas Hub

Turkey needs a transparent and scalable gas market, including the information and legal structure needed by non-commercial traders. For the market to be functional, price action must depend on market fundamentals, rather than speculation about the behavior of monopoly players. Turkey has twelve supply source countries including three via pipeline and nine via LNG. However, the near monopoly of state-owned BOTAS ruins the market structure. For price formation to occur, there must be competition in all the links of the supply chain including production, import, storage, and supply. In 2020, Turkey received ten points out of twenty in the annual European Federation of Energy Traders (EFET) gas hub survey - a significant improvement in only a few years (Chart 9). Despite its improvement, Turkey’s gas market remains far short of existing hubs and is not alone in its improvement (Chart 10).

Turkey has a well-established natural gas domestic distribution system but needs more flow capacity to meet export needs. Its system already bumps up against capacity limits on cold days with “line packing” being the go-to solution. Starting in 2016, Turkey began taking steps to increase flow capacity. Floating LNG regassification terminals and the TANAP pipeline were the first steps (Chart 11). The goal is to have sufficient excess capacity by 2023 to serve as a hub but the “expansion” barely keeps pace with domestic growth, meaning export capacity is being maintained not expanded. That also means Turkey needs help financing any major natural gas projects. That creates problems because the financiers are generally the producers, which puts Turkey right back where it started.

Geo-political Implications

There are, of course, huge implications for control over the east-west energy transport routes of Eurasia. Access to the energy itself, via pipelines, is a necessary step towards energy security but is not sufficient. To break the link between international politics and energy, the commodity must become fungible by being inputted to an arm’s length marketplace – a gas hub in this case.

Hosting a major hub brings with it not only prestige and supply security, but also easy access to a constant flow of dollars going through the banking system as a byproduct of contract settlement. Having an “offshore” hub would give Turkey the best of both worlds. Compliance with EU regulations would be optional but the need for energy security would bring with it implicit economic and diplomatic support from Western Europe. In addition, Erdogan would be the gatekeeper for energy suppliers looking to access European markets. The tables would have been turned.

Indeed, Erdoğan’s efforts to turn Turkey into a gas hub has already produced fruit in Europe. In December 2020, the EU elected to apply weak sanctions against Turkey for its actions in the eastern Mediterranean. EU members have diverging interests regarding Turkey, so the sanctions have no clear direction. The EU has tolerated Turkey’s actions towards Greece and Cyprus for years and accusations have been made that Germany’s interests are being placed above theirs. Turkey and Germany share a need for imported gas, specifically gas from Russia.

Germany also has ambitions about becoming an energy hub for Europe. Mattais Warnig, CEO of Nordstream 2, said the pipeline would make Germany an energy hub for Europe. The German Foreign Minister said at the same press conference that “sanctions between partners are, of course, the wrong way.” It was Germany that blocked harsh sanctions against Turkey at the European Council summit. Ensuring special accommodations are made for gas hub countries is in Germany’s interest. It should also be noted that millions of Turks migrated to West Germany after World War II to fill the labor market void. The diaspora and their descendants now account for five percent of Germany’s population and are a recognized force on the political scene.

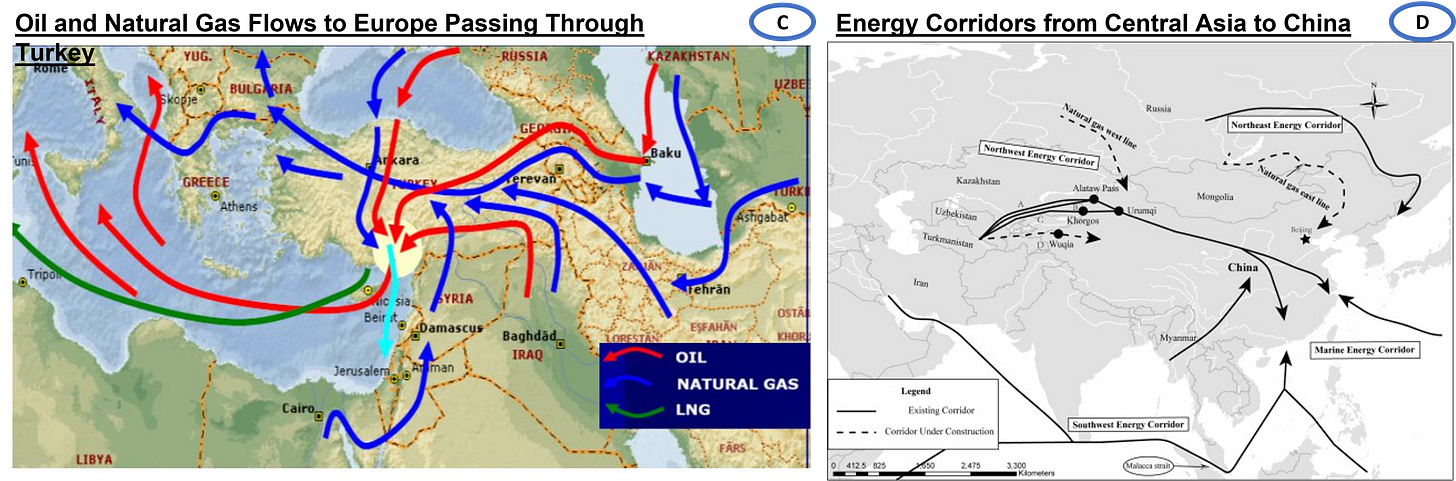

There is also a race to create the infrastructure and economic conditions necessary to draw energy flows in the first place (Maps C and D). During the last twenty-years, haggling, intrigue, and disappointing economic performance have limited energy flows from Central Asia to Europe. During that time, China’s hands have not sat idle. The result has been a massive redirection of energy flows from Russia, Central Asia, and the Middle East to China. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has generated strong momentum (perhaps too much) in building eastward-flowing energy flows. Competing for Central Asia’s energy resources will require much more diplomatic and economic enticement now than it would have twenty years ago.

Conclusion

In Part 1, we explored the weak points of the Turkish economy and its chronic dollar deficit problem. In this note, we explored why Turkey’s energy imports are so problematic. The reliance on pipeline gas negotiated through bilateral deals leaves Turkey largely at the mercy of its gas suppliers. Even with multiple suppliers and excess supply, Turkey’s relative lack of bargaining power makes it an easy target for Russian “energy diplomacy”. The best way to stop this repeating pattern, for Turkey and the EU as a whole, is to break the relationship between natural gas and bilateral relations. Once natural gas becomes a completely fungible commodity, and a cheap one at that, the ability to apply bilateral pressure disappears. Once inputted into a hub, one country’s gas is the same as another’s and transactions take place at arm’s length. Of course, that has not worked out as Erdoğan had hoped and Turkey remains a mere transit country, neither a producer nor the host of a hub. As a result, Erdoğan has resorted to harder tactics to gain access to gas supplies in Central Asia and/or the eastern Mediterranean – the two triangles discussed in Part 1. Rising tensions and potential for conflict in the triangles will be the topics of upcoming notes.

Related Notes

Ottoman Dreams, Syrian Nightmares, and the Triangle Wars, Part 1

Cutting Up What Remains, Part 1

Cutting Up What Remains, Part 2

Cutting Up What Remains, Part 3

[1] See my Connolly Insight notes “The Hryvnia: Broken Country, Broken Currency”, PART 1 and PART 2 of 22 April 2014 and 6 May 2014.