This note was distributed to Premium Plus clients on 31 August, 2021. As mentioned in the Part 1, I am distributing it on Substack to provide background for upcoming notes to be released here in the future. New readers are entering an ongoing conversation with my advisory clients that, in some cases, has been going on for more than a decade. I do also want to highlight the durability of my research, which provides understanding rather than “forecasts” that are of no practical use to anybody anywhere.

What images come to mind when you think of the Nile River? Is it towering green mountains and fertile lowlands fed by huge amounts of rain? Probably not - unless you are from Ethiopia – and that is just how Egypt wants it. In the modern era, Egypt has enjoyed the position of Hydro Hegemon among the nations of the Nile River Basin. But Ethiopia is in the final stages of a project, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), that could crown a new hegemon of the Nile. Part One of this note examined events in Ethiopia and Egypt leading up to the current conflict. This note examines the struggle for hydro hegemony in eastern Africa, as well as the larger geo-political implications.

Hydro Hegemony

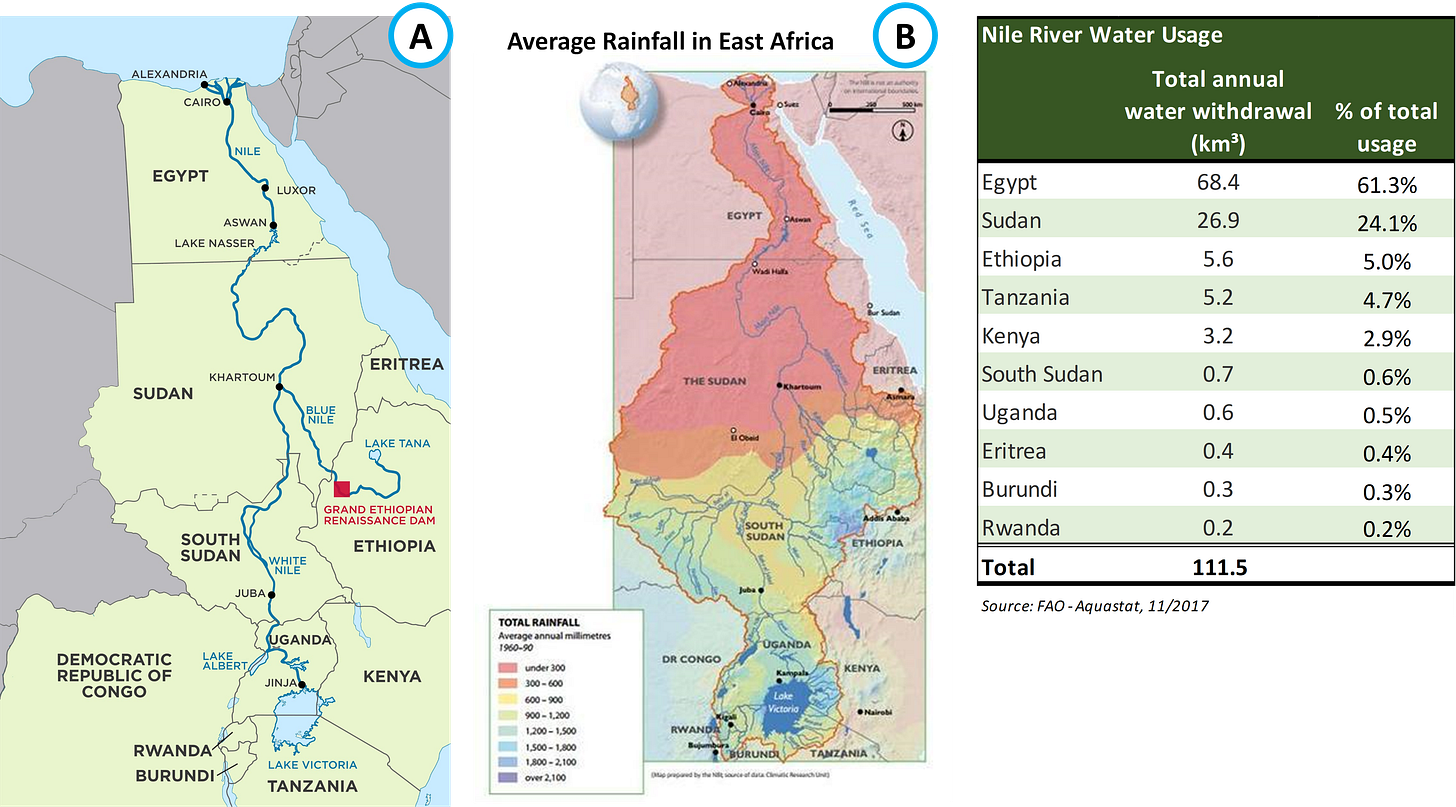

Among the Nile countries, Egypt is last in line (Map A), provides almost no rainwater to the river (Map B), and has no alternatives to the river. But, as the hegemon of the Nile, the country uses more water than the rest combined and historically has had veto power over upstream projects. Power asymmetries determine the distribution of water resources, not international law, riparian position, or availability. Hydro-hegemons set the rules of the game, rather than use direct coercion, to achieve their objectives. Indeed, the most powerful tool the hegemon has is psychology. Through rhetoric and symbolism, a hegemon instills a sense of “natural order” about the status quo.

Non-hegemons provide “apparent consent” to the status quo by limiting their water usage and refraining from water development projects. This has historically been the relationship between Egypt and the other Nile Basin countries. The upstream countries have never been able to create a lasting united front. But non-hegemons can improve their bargaining position by constructing infrastructure and forming alliances against the hegemon. Taking the effort one step forward, a non-hegemon can seek to “liberate” itself by changing the rules. This is the situation playing out on the Horn of Africa where infrastructure development, diplomacy, and treaties have been deployed to challenge Egypt’s status.

The Rainmaker

The highlands of Ethiopia are known as the water tower of east Africa because they stand with the rainforests of central Africa in terms of annual rainfall (Map C). Ethiopia’s topography is defined by two highlands separated by the Great Rift Valley (Map D). Because it sits in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, weather approaches the country from the north or south, depending on the time of year. As a result, Ethiopia has two rainy seasons that affect the north and south at different times of year.

Ethiopia’s belg rains fall on the southern half of the country from February to May. About ten percent of the population is completely dependent on this seasonal rainfall (Map E). The kiremt rains, which account for fifty to eighty percent of annual rainfall, fall on the northwest of the country from June to September (Map F). Because its highlands tower over east Africa and because the country receives more rain than the ground can soak up, Ethiopia is the origin point for numerous river basins. These rivers provide water to the entirety of east Africa, and many are just as important to their downstream countries as the Nile is to Egypt (Map G).

This is where the geostrategic element of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam becomes apparent. Originally, GERD was seen by the international community as a way for Ethiopia to make use of its water resources and force Egypt to accept a more “equitable” distribution of the Nile’s waters. Egypt was seen by many as a negative hegemon and Ethiopia marketed GERD as a means to change that. International experts applauded GERD when it was proposed, and other Nile Basin countries reacted positively – even Egypt was willing to listen.

Wheelin’ and Dealin’

The upstream-downstream argument stems from a lack of established procedures for constructing and operating upstream projects. Without a standardized framework, upstream countries were forced to ask permission and negotiate with Egypt and Sudan on every Nile-related project. The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), founded in 1999, was the first serious attempt by the upstream countries to change the rules of the game. All nine Nile countries are members, including Egypt and Sudan, and the initiative is backed by the World Bank.

For a decade NBI members negotiated the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA), a set of rules governing use of the Nile that would end Egypt’s role as hegemon. The agreement was finalized in 2010 and, despite Egypt and Sudan walking out, seemed to be a success. However, Egypt was able to nullify the CFA by putting a lot of diplomatic work into building close relations with most of the other Nile Basin countries. In the end, the CFA was only fully ratified by Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Tanzania.

From 2011, when construction on GERD began, until the African Union (AU) summit in June 2014 Ethiopia tried to sell the project to downstream countries, especially Sudan, by emphasizing benefits. In 2012, then-President of Sudan Omar Bashir endorsed the project, marking a major shift in negotiating power towards Ethiopia. At the time Sudan was struggling to restructure its economy after two-thirds of its oil reserves disappeared when South Sudan seceded. However, winning over Bashir marked the high point of Ethiopia’s public relations campaign. Having failed to gain widespread support for GERD, Ethiopia opted to proceed unilaterally. At this point the situation switched from Ethiopia trying to bring Egypt to the negotiating table to the reverse.

Egypt saw the risk of Ethiopia becoming a new hegemon and began putting effort into creating a diplomatic climate where a binding agreement could be created. Having accepted GERD as a fact on the ground, Egypt wants to prevent Ethiopia having discretionary control over the flow of the Nile. After pushing for a restart to negotiations Egypt was able to negotiate the ‘Declaration of Principles’ agreement with Sudan and Ethiopia in 2015. The agreement is meant to be a framework for negotiations that puts the recommendations of an Independent Panel of Experts (IPoE) at the center of discussions. Egypt agreed not to impede Ethiopia’s “developmental needs” and Ethiopia to avoid “any potential adverse effects…” on Egypt. However, the statement is political rather than technical, so it is vague on some important points and silent on others.

Negotiations continued but were simply a ploy for Ethiopia to delay while construction proceeded at full pace. Ethiopia’s intransigence was clear in its refusal to make any concessions, even on secondary issues. In an effort to bridge the gap in negotiations, Egypt offered to provide financing and technical expertise in managing operations of the dam. The proposal was swiftly rejected on the grounds that operation of the dam was a matter of national security. For Ethiopia’s neighbors, the choice of national security as a justification was very telling, and their positions began to change.

Wants and Needs

There is no doubt that Ethiopia needs to improve its dam infrastructure. The cost of variability in water supply is a high one for Ethiopia, estimated at one-third of potential GDP growth. Agriculture is a major component of Ethiopia’s economy, representing 40% of GDP, 90% of exports, and 85% of employment. But Ethiopia has less than 1% of the water storage capacity per person than exists in North America. Having reservoirs will provide the regularity of water flow Ethiopia needs to increase its irrigation infrastructure and move away from rain-fed agriculture.

Famines in the 1970s and 1980s toppled successive governments and the EPRDF, Ethiopia’s ruling party in the 1990s, wanted to avoid the same fate. In a first for Ethiopia, the government formed a coherent and ambitious water development policy. The Water Sector Strategy of 2001 emphasized development projects on the Blue Nile, which represents 45% of Ethiopia’s accessible surface water. Dam projects were seen as vital to providing electricity and irrigation needed to modernize. At the time Ethiopia had only a few small dams producing a combined output of 400MW - only 3% of Ethiopia’s hydropower had been developed. By 2015 there were 15 projects either planned or already under construction. During the 2010s the water security plan drove a “dam boom” that converted debt financing from China into artificial prosperity (Chart 1).

Sudan has three dams and one irrigation project that are directly affected by GERD. The Gezira irrigation scheme is one of the largest in the world. Gezira uses thirty five percent of Sudan’s allocation from the Blue Nile and serves one hundred twenty thousand farmers. That project is approximately half of Sudan’s total irrigated farmland. Irrigated areas represent seven percent of Sudan’s farmland but produce fifty percent of agricultural output. Under normal conditions, GERD will reduce the seasonal variability Sudan must deal with and allow for an expansion of irrigation. Sudan will also benefit from the electricity produced by GERD. Only 45% of the population has electricity coverage – 70% of the urban population and 30% of the rural population.

For decades Egypt has used Nile water to sustain a large population of low-productivity micro-farms. In 2005, then-Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi highlighted the issue when he said, “Egypt is taking the Nile water to transform the Sahara Desert into something green.” While Ethiopia is “denied the possibility of using it to feed ourselves." Egypt’s counter argument is that without GERD Ethiopia already has access to 122 BCM of non-Nile River water and 1600 BCM of rainwater. Both sides see their own needs as equivalent to rights to the waters of the Nile - and the needs of other Nile countries merely as wants.

One Man’s Right…

The treaties that Egypt and Sudan have based their argument on are controversial. The oldest is a 1902 treaty between Britain (on behalf of Sudan) and Ethiopia that required the later “not to construct…any work across the Blue Nile, Lake Tana, or the Sobat, which would arrest the flow of their waters into the Blue Nile, except in agreement with Britain and Sudan.” In 1929, Britain (on behalf of Sudan) and Egypt signed an agreement on minimum water allocations to the two countries. The treaty declared the “natural and historic rights” that the two countries had on the waters of the Nile. In 1959, tensions between Sudan and Egypt grew over the latter’s construction of the High Aswan Dam. To ease tensions the two countries allocated themselves annually 55 BCM and 18.5 BCM of river water, respectively.

Except for the inclusion of Ethiopia in 1902, none of the treaties considered the interests of the upstream countries. Naturally, the upstream countries object to the colonial era agreements and want to change the status quo. In March 2021 the Ethiopian Foreign Ministry said, “this tendency to adhere to agreements of the colonial era…is unacceptable.” But to be willing to sign a new agreement Egypt and Sudan want an emphasis on their “acquired” and “historic” rights to the Nile’s waters. Those are established legal principles that mean “first in time, first in right”, which is a recognized factor in assessing “equitable utilization”. However, recognition of historic rights would simply be a continuation of the status quo.

During the twentieth century, the apparent acceptance of the status quo by the upstream countries was the result of a large economic development gap between Egypt and the rest of eastern Africa. In Ethiopia’s case, until the late 1990s the country lacked the diplomatic, technical, and financial resources for major projects. Successive governments talked about water security, but no coherent policy was implemented. The lack of policy was seen as “implied consent” to Egypt’s position as hegemon, but Ethiopia’s real position was one of “veiled contest”. They just were not putting up much of a contest.

Four Dams in One

As mentioned above, Ethiopia’s challenge to Egypt’s hegemony was initially applauded but, only recently, it became clear that Ethiopia is looking to replace Egypt as the hydro-hegemon of the Nile. The ultimate goal of GERD to create a new-unequal order, rather than an equitable distribution. Ethiopia’s Foreign Minister spilled the beans in July 2020 when he said, “The Nile used to flow and now it has become a lake, from which Ethiopia will be able to achieve its desired development. The Nile is ours.” Ethiopia has been building GERD as quickly as possible without a legal framework in place to create “facts on the ground”.

The stated economic goal of GERD is to make Ethiopia the electricity hub of east Africa via exports of hydropower. But according to the IPoE report the economic benefits of GERD for Ethiopia, relative to cost, are nonexistent. The price of electricity in the region is expected to plummet as huge hydropower projects across the basin come online. The World Bank has encouraged Ethiopia to build multi-use dam projects along the Blue Nile to make the country “water resilient”. The World Bank and other international organizations refused to fund GERD because it was built for electricity only.

Even the design of GERD has drawn suspicions about Ethiopia’s true intentions. In response to Soviet backing of the High Aswan Dam in Egypt, the US Bureau of Reclamation conducted surveys from 1958 to 1964 for potential dam locations. The project was billed as providing Ethiopia “full utilization” of its waters. Four dams were suggested that would hold a combined 73 BCM and produce 5570 MW of electricity – very close to GERD on both measures (Map H and table).

The proposed location of the westernmost of the dams, Border Dam, is the site chosen for GERD. The proposed height of the Border Dam was limited to eighty-five meters because anything higher would have required an expensive “saddle dam” to fill in a gap in the gorge that forms the reservoir. GERD’s tremendous size required an additional fifty-meter-high saddle wall, increasing cost and reducing return. Electricity production is only able to operate at peak capacity two months per year, leaving much of the equipment idle the rest of the year. The smaller Border Dam was the optimal size.

All these factors make GERD a geostrategic objective, rather than a developmental one. The location of GERD is based on the USBR surveys, but the scale was driven by the goal of achieving political power by building a massive project on the Nile. The dam has value above and beyond its economic value. As a result, Ethiopia is willing to pursue the project regardless of the commercial feasibility, technical difficulty, or environmental/social impacts.

Shifting Winds

The growing realization that Ethiopia is positioning itself as the new hegemon of the Nile has steadily brought the other Nile Basin countries into Egypt’s camp. Negotiations between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan have effectively been put on hold since early 2020. Since then, Ethiopia has been coming up with a list of excuses for not negotiating and the international community’s patience is wearing thin.

New progress in negotiations seemed possible in early 2021 when the Democratic Republic of the Congo took over the rotating Chairmanship of the African Union and the Biden Administration entered office. The Trump Administration’s open support for Egypt’s position on GERD led Ethiopia to reject the U.S. as a mediator. In February 2021, as a show of good faith, Biden reversed Trump policy and restarted foreign aid to Ethiopia. That month Sudan called for the GERD negotiations to be widened to include the EU, US, and UN. Egypt was initially skeptical of Sudan’s call to widen the negotiations but accepted the plan after deciding it would be good way to increase pressure on Ethiopia.

The Biden Administration was able to negotiate an agreement between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia to resume negotiations based on the recommendations of the Independent Panel of Experts. But, once again, Ethiopia walked out of discussions. In March 2021, Egypt and Sudan signed a security alliance. Described as an “unprecedented level of military cooperation…at a time when Egypt and Sudan face common challenges and multiple threats.”

Further AU talks were held in DRC in April 2021, but no consensus was reached. The Egyptian technical delegation was tasked with providing several alternative solutions to the outstanding issues. Sudan and all observers to the talks backed Egypt’s proposals – only Ethiopia refused all of the options presented.

Ethiopia has cited Article 10 of the Declaration of Principles on the GERD, signed in 2015, as its justification for rejecting mediation. Article 10 allows a party to effectively keep negotiations open indefinitely. Ethiopia wanted to drag out the AU negotiations because only after the regional organization declares the talks failed can the matter be referred to the Security Council.

Egypt and Sudan have taken the position that the US, EU, and UN must be involved for any further talks with Ethiopia to take place. Egypt had been pushing for the AU to declare the negotiations failed so that the matter could be submitted to the UN Security Council. In July 2021, the GERD dispute was brought before the Security Council but sent back to the African Union negotiations with instructions to try harder. Thus far, support from Russia and China allowed Ethiopia to proceed with GERD despite the disapproval of the other members of the UN Security Council.

The Death Star

Egypt and Sudan have good reason to be concerned about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam because in the wrong hands or under the wrong conditions the dam could be the end of them. One of the reasons the USBR designed four medium sized dams was for safety. In the event GERD fails, it would produce a wave that would successively top each of Sudan’s three dams on the Blue Nile, adding their reservoirs to the flood. A fourth dam on the White Nile would also likely fail due to a negative surge wave. All of Egypt’s dams on the Nile would fail as well. Ethiopia is located on a plateau that looms above its neighbors at an average height of 600 meters. The deluge from a dam break will hit Sudan at high-speed, minimizing warning time and maximizing destructiveness. After four days the water would reach Khartoum and peak at a depth of fifteen meters as the wave passes through.

Thirty five percent of dam failures are caused by long periods of rain that exceed spillway capacity. The spillway for GERD can handle two to three days of rain falling at a rate of 2,500mm per day. The average high for annual rainfall in Ethiopia is 2,250mm in one day. Cutting it rather close! Another major cause is earthquakes. GERD is located on a fault line that experiences more than ten thousand (mostly small) earthquakes each year. Even if the earthquake does not destroy the dam directly, it can cause a landslide in the reservoir gorge that could cause a dam-breaking wave.

Short of outright failure, even simple mismanagement or lack of scruples can have catastrophic effects for downstream countries. Lake Turkana in Kenya is currently at risk of a slow death caused by Ethiopia’s Gibe III dam on the Omo River. The Omo is the only source of water for Lake Turkana, which loses 2.3 meters of water to evaporation each year. If Ethiopia restricts flow of the river during a dry period, the level of the lake could fall, and water salinity would rise. The livelihoods of over five-hundred thousand farmers and fishermen in Kenya are threatened by the dam.

To prevent damage to downstream dams and agriculture, close cooperation – if not collaboration – are necessary. But Ethiopia’s track record gives reason to doubt such cooperation will be forthcoming unless it is legally required. In 2021, Ethiopia began preparing to fill the dam in April for a May/June start but, to avoid damage to their own dams, Sudan and Egypt need more notice.

Even assuming GERD is managed properly and data on operations are exchanged, if the fill rate of the reservoir is too fast there can be disastrous consequences for the downstream countries. If the fill rate is less than five years, or if there is an extended drought, the availability of water for irrigation could fluctuate. In the hot Sudanese sun, even a brief interruption of irrigation would result in massive crop loss.

Because the first filling was done in a wet year, the effects should be limited if the other years receive at least average precipitation. But if the filling occurs over the course of four consecutive dry years, the reservoir at High Aswan Dam (HAD) would reach its operating minimum. Little power would be produced, and water outflow would need to be limited, reducing downstream supply significantly. Even under the best circumstances electricity production at HAD will permanently be reduced by 5-10%.

For Sudan the effects of GERD are very mixed. The current limit on irrigation in Sudan is a lack of reliable water supply, not a lack of arable land. Only 22% of Sudan’s arable land is currently used. By smoothing out the yearly flood, GERD will provide Sudan with a more stable flow of water year-round. Irrigation could expand because regularity of flow would be improved. But, in a five-year fill scenario, a reduction in the river’s flow rate, possibly 42%, will increase evaporation losses in Egypt and Sudan. Higher levels of evaporation lead to higher water salinity, causing problems with soil saltification.

GERD will also reduce the flow of silt, which cuts both ways for downstream countries. Cutting silt flow will reduce buildup in the reservoirs of dams in Egypt and Sudan. That will reduce maintenance costs and increase electricity output. However, it comes at the expense of losing the traditional flood of fertilizing silt that flows down the Nile during the upstream rainy season. The High Aswan Dam destroyed the fertility of Egypt’s downstream farmland forcing famers to use massive amounts of fertilizer use to get crops to grow in the desert. The reduction in silt had a major economic and environmental cost to Egypt.

If there are no natural or man-made disasters, and all participants cooperate, there remains the threat of a long drought. The first filling of GERD took place in an unusually wet year, but effects on the river were easy to observe at HAD (Chart 2). In 2020, the size of the reservoir was drastically lower than a projection based on the prior trend. That was a wet year, and the Horn of Africa is no stranger to dry years. Indeed, Ethiopia experienced a drought in 2015 that was on the magnitude of hundreds of years for expected occurrence. Normal drought conditions were multiplied by an Indian Ocean El Nino. Dry conditions led to failed crops and depleted livestock. Eight million people needed emergency food aid.

Fortunately, the 2015 drought was limited to one bad year, but Ethiopia has not always been so lucky. The period from 1975 to 2000 was “super drought” that yielded multiple famines (Chart 3). The good news is that GERD would make such events a thing of the past in Ethiopia. The bad news is that unless there is extensive cooperation and preparation the risk of a super drought is simply pushed downstream. Without a binding agreement Ethiopia could hold the downstream countries hostage for decades in the event of a long drought.

Nile Diplomacy

Ethiopia’s obstructionism in the GERD negotiations and lack of scruples for Kenya have not gone unnoticed by other countries. Nor did a May 2020 speech by Abiy in which he promised Ethiopia would start construction on one-hundred small and medium-sized dams in 2021. The promise was an unrealistic one, but the statement was meant for domestic consumption, indicating what the Ethiopian public wants.

Egypt has been working to isolate Ethiopia diplomatically by fostering strategic relationships with all its neighbors. Kenya and Egypt signed an expanded defense partnership agreement in May. That marked the fourth defense partnership agreement in 2021 for Egypt. Egypt has formed defense partnerships with Djibouti, Eritrea, Burundi, Somalia, and Sudan. Alliances and mutual defense pacts crisscross the Horn of Africa.

Egypt and Sudan have grown very close since the Islamist Omar Bashir was overthrown in 2019 and a secular military junta took over. Sudan is looking to clear its debts to financial institutions and official bilateral creditors (China), which amount to $50 billion. With strong diplomatic backing by Egypt and a military junta that knows how to satisfy Western governments, Sudan has done much to polish its international image. U.S. Secretary of State Blinken said in March 2021 that there is a “new chapter” in US-Sudan relations after Sudan paid $335 million in damages to victims of terrorist attacks. The payment made Sudan eligible for the Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and the World Bank has said Sudan is on the path to substantial debt relief.

The international community has been focused on ending sanctions and providing debt relief to Sudan because, until the war in Tigray broke out, it was the country on the Horn closest to the brink of failure. However, instead of taming the junta, international approval has only made the military stronger. The civilian-military power sharing agreement stipulated the Rapid Security Force (aka. the Janjaweed) be integrated into the regular army. But, according to RSF leader Mohamed “Hemeti” Dalgo “Talk of RSF integration into the army could break up the country.” Prime Minister Hamdok has also made mention of “deeply worrying” fractures in the national security apparatus. The civilian government of Sudan is a sham, the military is the only authority that matters.

In March, Sudan’s government signed a peace agreement with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North. The group had fought against the Bashir regime’s Arabization policies for decades to maintain their African heritage. Rather than being disbanded, the SPML-N will provide a major boost to the strength of the regular Sudanese army. Sudan has moved its irregular militia forces into position for a thrust into Ethiopia. The two countries are at odds over the al-Fashqa border region, claimed by Sudan based on the 1902 treaty between Britain and Ethiopia. Ethiopia accused Sudan of taking advantage of the war in Tigray to grab disputed territory in the al-Fashqa area, which abuts the Ethiopian states of Tigray and Amhara. To block the Sudanese militia Amhara militia entered the triangle and were engaged by the Sudanese military.

Sudan’s mousetrap has already been loaded. If Sudan’s militias see an opportunity to make a land grab while there is chaos in Ethiopia, neither Sudan’s government nor its military could stop them. By the same token, the speed and aggression of the Janjaweed is exactly what Sudan and Egypt want if they need to make a grab for GERD. Neither country wants to go to war but, as discussed above, a failure of GERD would be an existential event for Sudan and Egypt. Ethnic violence is taking place in Benishangul-Gumuz, the region of Ethiopia where GERD is located, and an armed group was able to take control of several cities in April 2021. GERD is just across the border from Sudan so a fast-moving irregular force that lives off the land could make a grab for the dam if Ethiopia’s civil war puts safe operation at risk.

The Gathering Storm

Global stability had become tied to an extremely unstable corner of the world – the Horn of Africa. Contests for strategic control of the Red Sea and eastern Mediterranean have brought the world’s Great Powers to the tiny enclaves of east Africa. Any war on the Horn of Africa risks widening into a regional war in short order as numerous defense agreements crisscross the region.

Egypt and Sudan want to avoid being held hostage for water by Ethiopia or falling victim to a disaster of epic proportions. Short of these scenarios, I do not expect offensive action to take place as a result of Ethiopian intransigence in negotiations. If political conditions and rainfall in Ethiopia were both stable indefinitely Egypt would seek secure its position at the negotiating table. But the stability of those two factors cannot be taken for granted.

The possibility of a long and ugly civil war in Ethiopia is a very real one, which could put safe operation of GERD into doubt. If political deterioration does take place events will be fast moving and Egypt will not have time and diplomatic space for the huge wind-up necessary for a conventional military invasion. Instead, Egypt will make use of Sudan’s fast moving militia forces.

Another potential flashpoint is an invasion of the Somali state of Ethiopia, which is home to many ethnic Somalians. Indeed, Somalia invaded Ethiopia in 1977 to capture the Somali-majority regions. It was only with the help of twelve-thousand Cuban troops, and fifteen hundred Soviet “advisors” that the Somali forces were pushed out. If the civil war in Ethiopia gets uglier, an intervention by Somalia would internationalize the conflict rapidly. Turkey has been working on a Turkish-trained Somalian Expeditionary Force and holding GERD would be a massive prize for Erdogan to hold over his archrival Sisi.

Conclusion

Events with security implications on the Horn of Africa have extra significance now that the Great Powers have taken an active interest in the Red Sea. When you have multiple Great Powers operating in a small space with guns drawn, every minor security incident becomes a small emergency. Operating in that tense environment are the leaders of several small unstable countries, all of whom have a thousand old scores to settle. Will the leadership of Somaliland become comfortable officially seceding from Somalia once Egypt and UAE have an airbase there? Could the tiny nation of Djibouti try to retake disputed land from Eritrea now that the former hosts military bases of the U.S., France, Japan, Italy, Spain, China, and Saudi Arabia?

Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s internal turmoil is preventing Abiy from making concessions with Egypt and Sudan on the GERD project. The building of the dam with domestic resources, after decades of Egyptian obstruction, is a symbol of national pride. The project is hugely popular in Ethiopia and there is significant symbolic power for whoever controls the dam. By the same token, the dam will eventually provide geopolitical power as it could allow Ethiopia to force Egypt to buy water.

Other nations on the Horn have come to realize Ethiopia’s underlying goals and fear their water supplies will be held hostage next. If Ethiopia does become hostile over control of the flow of water, it will quickly be surrounded by threatened downstream countries. Normally international laws, multilateral negotiations and other normative measures would keep the situation under control, but Ethiopia is a hot mess that could fall apart politically. As said by the U.S. Secretary of State, Ethiopia could make Syria look like “child’s play”. A deterioration in security conditions in Ethiopia will herald a deterioration in security across the Middle East.

If you enjoyed this note please click ‘Like’, or share it with others who might be interested. Subscribers are encouraged to not only sound-off in the comments, but also post follow-up questions and potential topics for future research.