The Red Sea, the White Nile, and the Blue Peoples

What do Emperor Justinian and Elon Musk have in common?

This note was sent to Premium Plus subscribers on July 20th, 2019. I am distributing it here as part of a series about the geopolitical situation on the Horn of Africa and in the Red Sea. Readers can look forward to more notes on this topic.

The Saudis’ need for mercenaries in Yemen makes developments on the Horn of Africa of vital importance. Without a flow of soldiers for-hire from Sudan the Saudis cannot sustain ground combat in Yemen so they will lose the war by default.

South Sudan has taken on global importance because it holds the oilfields that are the lifeblood of Sudan’s petrodollar economy. If the military regime in Sudan feels they are losing control, they will have every reason to reach out and easily take back their source of power. More importantly, the military regime will do so with the backing of the Saudis.

A Trump win in the 2020 election means there will be no impediment to increasing US oil production. Clearly, the Trump Administration would not shy away from a production goal of twice the size of Saudi Arabia or Russia.

Once the uncertainty of US backing becomes clear to MBS, if it has not already, he will realize that a countdown to survival for him personally has begun. If he wants to become King of Saudi Arabia, which is his best chance of living to forty, he must provoke a war between the US and Iran before his time is up.

The streets of Khartoum are soaked in blood. The authorities think they’ve washed it away, but you never really get it all. It seeps into the cracks and soaks into the pores of the pavement. Unfortunately, for the living, the blood spilled in Sudan over the past six months will not be the last. The agreement struck between the divided civilian leadership and the military will break down because it does not address any causal factors. For the wider world, the concern should be that conflict in the Horn of Africa is becoming a potential inception scenario for a regional war in the Middle East. Unlike conflicts closer to home for the GCC countries (i.e. Syria), proxies control the action on the Horn of Africa.

The shift in US foreign relations to a bilateral framework by the Trump administration has changed the strategic landscape. On the Horn of Africa, the Saudis and UAE are facing off with Turkey and Qatar in competition for strategic assets to be used in the larger struggle for regional dominance, which includes Iran as a third competitor. The scramble for control on the Horn has resulted in heavy use of mercenaries and anti-government rebels to advance the agendas of Saud/UAE and Turkey/Qatar. Iran currently has very little influence on the Horn after being elbowed aside by Saudi/UAE cash and investments.

As in the lead up to World War I, the layering of local conflicts with regional and global competition makes the situation potentially explosive. Small nations looking to settle scores begin operating under the assumption of backing by their patrons. The frequent, brutal wars that take place on the Horn were of little global importance until major powers began viewing military bases on the Horn as strategic assets. These local wars are just as likely to take place today as they were ten years ago, but now the stakes are much higher. Any war in the Horn of Africa risks pulling in regional or global powers on opposite sides of a local conflict. More importantly, a collapse of military rule in Sudan will likely cause aggressive action by the Saudis in an attempt to start a war with Iran before the US and UAE move to a more conservative policy of containment for Iran.

There are four layers of conflict playing out on the Horn. The top layer comprises global powers competing for influence and protecting their imported energy resources. The second layer is the Not-So-Cold War between the Saudi Arabia and Iran. The third layer is inter-Sunni relationships, most-notably the Saudi/UAE conflict with Turkey/Qatar. At the bottom layer are numerous local-level issues between state and non-state actors on the Horn. In this note I will discuss the web of rivalries and alliances that regional and world powers have gotten themselves stuck in and potential inception scenarios for a regional war.

The Yemen Connection

In the war in Yemen, the agendas of Mohammed Bin Salman, Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, and Mohammed Bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi (i.e. the emirate that calls the shots in the UAE) are aligned, but not identical. The Saudis want to corner the Houthis and set up conditions for a negotiated peace. MBS must eliminate the threat to the homeland posed by the Houthis and secure the Arabian Peninsula (Map A).

In contrast, the UAE is geographically insulated from Yemen so missile attacks on the homeland are a less-immediate threat (Map B). For the UAE, the war in Yemen is primarily about security for oil tankers traversing the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea on their way to the Suez Canal. Houthi missile attacks on Saudi Arabia’s only pipeline to the Red Sea and the ongoing harassment of tanker ships south of the Strait of Hormoz are a message to UAE that their efforts in Yemen and on the Horn of Africa cannot guarantee security for oil shipments.

The Saudis are worried the Houthis will evolve from a poorly equipped extended family into a Hezbollah-style paramilitary group, right on the Saudi border. That transformation is taking place right before the Saudi Crown Prince’s eyes and it can only be achieved with tactical expertise from Hezbollah and technical expertise and materials from Iran. For Abu Dhabi, the threats of a steady stream of missile attacks, running out of cash, and major domestic unrest are much more remote than they are for the Saudis. If the Saudis cannot provide a secure route, the UAE is much better off making deals with Qatar and Iran through Dubai’s close connection with those two countries. Mohammed Bin Salman has good reason provoke a conflict with Iran before the UAE starts making deals and Trump decides enough oil can be produced domestically. Making other countries handle their own security and encouraging domestic energy productions are both priorities of the Trump administration. Even MBS knows that water flows downhill. Leaving the Saudis to fend for themselves is becoming the path of least resistance for a growing list of people and governments.

The war in Yemen has gone completely wrong for MBS and events are unfolding in a way that doing something desperate becomes the path of least resistance for him. The Houthis are the strongest force in Yemen, with 100,000 soldiers and a growing arsenal of simple but effective flying bombs. The Houthis have yet to suffer a defeat in their mountain strongholds and the more of a problem they make themselves to the Saudis, the better friends they become with not only Iran, but now also Turkey and Qatar. As discussed above, the UAE only needs to control a small amount of territory in just the right places. The UAE can afford to play defense at this point; the Saudis cannot. As a result, the UAE has become a close ally of the southern separatists, who are willing to abandon the areas of Yemen controlled by Al Qaeda or the Houthis. The separatists have been working to ignore the Saudi-supported ex-President Hadi and set up their own South Yemen government in Aden. The separatists only number about 30,000, but the UAE has supplied air support and special forces to assist in difficult missions, as well as funding radio and television stations for the separatists. If the separatists are able to capture the Port of Hodeida on the Red Sea, circled in red below (Map C), the UAE will have met enough objectives to negotiate peace with the Houthis. Such an outcome would leave the Saudis and their mercenaries facing the second most powerful group in Yemen, the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated al-Islah party. The al-Islah party’s forces have been the most effective at fighting the Houthis and their militia has grown to over 100,000. For now, the Saudis and al-Islah have aligned agendas in Yemen: defeat the Houthis and keep Iran out. However, if a partitioning of the country looks likely, the Saudis and al-Islah will suddenly have opposing interests and will turn on each other.

UAE and Saudi Arabia have made extensive use of mercenaries in Yemen. Eritrea and Sudan have provided ground forces to the Saudis. UAE has been hiring higher-quality mercenaries as “hit teams” targeting high-value individuals. Getting involved in Yemen provided Sudan with much-needed cash from Saudi/UAE and helped ease US sanctions. In 2016 the Saudis switched five billion dollars of military aid from Lebanon to Sudan. Siding with the Saudis also helped ease pressure Egypt was putting on Sudan over Nile water usage. However, the move was very unpopular in Sudan and played a major role in the protests that brought Bashir down.

It is the Saudis’ need for mercenaries in Yemen that makes developments on the Horn so important. Without a flow of soldiers for-hire the Saudis cannot sustain ground combat in Yemen so they will lose the war by default. The reason Sudan is so important is that Egypt and Pakistan have refused to send troops. Sudan currently has approximately fifteen thousand troops in Yemen. The soldiers are primarily Janjaweed militia as well as regular Sudanese the Saudis hire for ten thousand dollars with a twenty-five thousand dollar payout at the end of a year or thirty-five thousand dollars to the family if the soldier dies. Twenty to forty percent of the Sudanese “soldiers” are children under sixteen.

Riyal Politik

Political systems in the Arab world generally involve a ruling caste that exploits state resources and represses political rights. The ruling castes are either dynastic monarchies or “democracies” with ruling military and bureaucratic classes. Since the “Arab Spring” of 2011, outcomes of rebellions have depended on the type of ruling class each country had. The monarchies have called on their praetorian guards to crush any opposition forces. In contrast, with military-security states the leader and his cabinet are only the tip of the iceberg in a larger power structure. The “deep state” of the military-security state (i.e. high-level members of the military, internal security, intelligence services and bureaucracy) quickly disposed of the embarrassing dictator to try to save themselves. Many of the military-security states collapsed and were reborn under new leadership, such as Mubarek and Sisi in Egypt.

Thus far, Sudan has followed the path of prior military-security rebellions. However, it appears the civilian revolutionaries in Sudan learned the two most important lessons of the Arab Spring. First, the entire security complex must be replaced by civilian rule. Second, a short transition period plays into the hands of reactionary forces. It takes time to build the political and state institutions needed to run a democracy. Indeed, Tunisia alone can claim success in bringing about positive political reform. The others have all slipped into chaos or returned to a Cold War-style military strongman. Only the Gulf monarchies currently have the domestic stability and cash to take decisive action, while the military-security regimes are in survival mode.

The Gulf monarchies are rentier states, which means very little capital is generated and reproduced through competitive activity (i.e. private capital). The state that funds the lifestyles of the people rather than the state taxing the people to fund itself. In these economies the ability to provide largesse is centered around the monarch and rents are parceled out as contracts, guaranteed market share or niche monopolies. Power is generally balanced across the family via control of economic resources. The same is true for foreign policy where foreign aid and “investments” are granted based on loyalty.

A system of patronage has developed to advance the interests of the GCC countries across the Middle East and Africa. Investments and grants are provided to governments and cash payments are made to non-state actors to buy loyalty (i.e. “Riyal Politik”). The GCC funnels money to client states via sovereign wealth funds, central bank transfers, economic development funds and investments by “private” companies, especially in real estate. The UAE-funded construction booms in Cairo and Khartoum are about bringing elite Egyptians and Sudanese into the UAE’s sphere of influence, not making money. Frequently private “charities” are used to launder money being sent to extremist groups by private citizens in the GCC.

International investments and development activity are directed by political needs, but they are funded by the sale of oil. As a result, the size and number of investments has risen and fallen over the decades with the price of oil (Chart 1). Since 2014 the Gulf monarchies have been cutting back on investment overall and have concentrated resources so that key allies have seen investment growth.

If Crown Prince MBS becomes concerned that chaos on the Horn, especially in Sudan, will weaken his position in Yemen (and against Iran) he is much more likely to take drastic action. The sections below discuss potential sources of conflict and disruption on the Horn in the order of least to most dangerous.

The Red Sea

For UAE and Saudi Arabia, the Horn of Africa is a means of supporting operations in Yemen and securing oil trade routes (Map D). Both countries have been very active in distributing guns and butter to gain new allies. For Turkey and Qatar, finding client states on the Horn of Africa to host Turkish military bases creates strategic assets. These bases will be useful in defending Qatar’s LNG trade routes and threatening Saudi/UAE use of the Red Sea.

Qatar has been very good at balancing its close relationship with the West and providing support to Islamist governments and “non-state actors”. That has allowed the tiny island to operate an outsized foreign policy without the diplomatic support of the Saudis. Qatar plays a major diplomatic and political role on the Horn. Doha has handled mediation for the conflict in Darfur, Djibouti-Eritrea and the US-Iran nuclear negotiations. Qatar has also supported “non-state actors” in Sudan, Somalia, South Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. Until recently, the Qatari/Turkish strategy seemed to be working. In 2017, Sudan granted Turkey a 99-year lease on Suakin Island, a former Ottoman stronghold on the Red Sea. The $650 million deal was financed by Qatar and includes a military-grade docking facility. However, Bashir’s overthrow puts the status of the lease into question.

To counter Qatar’s diplomatic heft, the Saudis have been working to create a multilateral institution on the Horn through their Red Sea Initiative. The first meeting was held in December 2018 and included representatives from Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Jordan, Egypt, Djibouti and Somalia. It remains to be seen whether the effort will bear fruit.

Below are two Red Sea hotspots that stand out as very problematic for regional stability. Neither of these hotspots are likely to directly trigger a regional war, but they will bring everyone involved further down the road to war.

Djibouti, Eritrea and Ethiopia

Since Eritrea declared independence in 1998, Ethiopia has been landlocked and dependent on Djibouti for ocean access. Djibouti now hosts many powerful foreign militaries, making it impossible to attack while simultaneously filling the government’s coffers. Tension rose when the small country began demanding better terms of trade from Ethiopia. Djibouti is only twenty miles away from Yemen at the narrowest part of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, one of the most strategic locations on the Red Sea. The country hosts military bases for the US, France, Italy, Japan and China. Turkey is in negotiations for a new base and the Saudis are planning to use Djibouti as their center of operations for Yemen and the Red Sea.

Through Dubai Ports, a private company with a habit of investing huge amounts of money in places of strategic importance, the UAE has been able to project a big diplomatic footprint in the Middle East. Dubai Ports was managing the Ports of Djibouti and Doraleh until the UAE refused to extradite the company’s CEO. The ports are now being run by a Chinese company and host the Chinese Navy.

To replace the loss of Djibouti, the UAE began looking for another partner on the Red Sea. The small, hermit nation of Eritrea was a potential partner, but first Eritrea would need to return to the international community of nations. At war with Ethiopia off and on since declaring independence in 1998, Eritrea was being crushed by diplomatic isolation and sanctions. The US, UAE and Saudi Arabia brokered a peace agreement in September 2018, in which Eritrea guaranteed Ethiopia access to its ports, UN sanctions were eased, and Ethiopia made a pledge of non-intervention.

Eritrea froze relations with Iran and began leasing the Port of Assab to the UAE Navy. The country opened its borders to Saudi and UAE forces and sent troops to Yemen. In return, the Saudis and UAE have revived the economy and government of Eritrea.

All seems well, but the Island of Doumeira, which sits in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, looms as a potential trigger for a confrontation. Djibouti and Eritrea last went to war over the island in 2008. Qatar mediated a peace between the two countries and sent troops to occupy the island. However, once the Saudi blockade of Qatar began, the peacekeeping troops were pulled out and Eritrea seized the island. A fight between the two small nations could draw Ethiopia into the conflict due to its hostile relationship with Eritrea. The UAE will then be faced with two unattractive options: defend Eritrea with force of arms or abandon a valuable strategic asset. Either option is a detriment to the Saudi/UAE condominium in its confrontation with Iran.

Somalia

Somalia’s national government has remained neutral in inter-Sunni competition between Saudi/UAE and Turkey/Qatar. However, five of the six regional governments have sided with the Saudis. After Dubai Ports was ejected from Djibouti, the company struck a deal with the regional government of Somaliland to upgrade and manage the Red Sea port of Berbera. The Somali parliament declared the deal void and expelled Dubai Ports from the country (noticing a pattern?). However, UAE continues to operate in Somaliland and Puntland in exchange for military equipment and cash payments. The regional governments receive no assistance from the national government and have few options for generating revenues. Economic activity generated by port construction and taxes on port traffic are a strong incentive to defy the national government.

Turkey has been playing an increasingly important role in Somalia, particularly in Mogadishu, since 2011, when aid was provided to avert famine. Turkey provided funds and capability to rebuild the air- and seaports of Mogadishu, which are now managed by Turkish companies. Taxing goods passing through the ports provides 80% of the national government’s revenue. Turkey also funded a 200-bed hospital in Mogadishu, the largest in East Africa. In 2017, Turkey opened a military base in Mogadishu under the auspices of training the Somalian National Army, but the base is designed to house a much larger and better equipped force than the Somalis will ever have. Presumably the goal is to base Turkish troops there.

The Somalis are forced to walk a thin line in the GCC conflict because, although Turkey is a major supplier of aid, Saudi Arabia and the UAE account for 80% of Somalia’s exports – mostly livestock and illegal charcoal for hookahs. In addition, Somalia receives tens of millions of dollars each year as remittances from the more than one million Somali workers in GCC countries. The UAE alone hosts over 100,000 Somali business diaspora operating their Somalia-based businesses from Dubai.

Another layer of complexity in Somalia is that most of the politicians and technocrats in Somalia are Islamists. Indeed, many of them studied in Sudan and returned more religiously conservative. In Somalia’s 2017 presidential election, Qatar/Turkey, UAE and Saudi Arabia all backed different candidates. The Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated incumbent was backed by Qatar and Turkey, while UAE sided with Sharif Sheik Ahmed, Somalia’s former president and a secularist. None of the candidates won an outright majority so the UAE switched support to the Saudis’ preferred candidate, and eventual winner, Mohamed Farmajo. Farmajo himself must walk a thin line between advancing the agendas of his backers while trying to avoid domestic unrest for the Saudi/UAE condominium in the inter-Sunni conflict.

If Islamists in Mogadishu object to Farmajo’s close relationship with the Saudis and UAE he could be replaced by an aggressive Islamist. An Islamist government friendly to Turkey and Qatar would likely try to bring the regional governments in line with the national government’s position. That would put Saudi Arabia/UAE and Turkey/Qatar on opposite sides of a Somali civil war. It is unlikely a war would break out between the external backers, but tensions will undoubtedly rise. More importantly, losing its port in Somaliland denies a major strategic asset from UAE.

The White Nile

Khartoum means “the place where the rivers meet” in the Nubian language of the pre-Arab tribes. Competition between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia over use of the waters of the Nile could trigger conflict on the Horn and deny the Saudis access to troops from Egypt or Sudan for several years, if ever. For decades Sudan sided with Egypt on allocation of water between the three countries. By siding with Egypt, Sudan denied Ethiopia full usage of its allocation of the waters of the Blue Nile for electricity generation and irrigation. The Saudis and the UAE compensated Sudan by providing two billion dollars to fund dam building on the White Nile and its tributaries.

Ethiopia has built a very large dam, the Grand Renaissance Dam (Map E), and can begin filling the reservoir at any time. The Ethopians have been waiting because the threats of economic and military consequences were too high to risk. In the past, the corrupt leadership of Sudan were happy to take bribes to deny Ethiopia the benefits of the dam. But for a civilian government focused on the good of the people filling the dam is a very attractive option because it will provide a large amount of cheap electricity.

Once operational, the dam will reduce the volume of water reaching Egypt by 10-20% for several years while the reservoir fills. A reduction of that magnitude would be catastrophic for Egypt’s power generation and agricultural production. The water was long ago allocated to Sudan and Ethiopia, but neither country had the means to use its entire allocation. Egypt’s leadership assumed that would always be the case and planned accordingly. That turned out to be a bad decision so Sisi been accusing Ethiopia of exploiting the weakness of the Morsi government to obtain approval for the dam project.

The outcome of the political transition in Khartoum is of existential importance to Egypt, and Sisi will act accordingly. If Sudan becomes a democracy instead of a military-security state Egypt will likely act unilaterally to crush the civilian government in Sudan. Power would then be handed back to the Sudanese military-security institutions.

A stable Sudanese military-security state backed by the Saudis would likely be acceptable to Egypt because the Saudis can use cash to balance interests. However, in past periods of civilian rule, the Islamists became the most powerful political party. In each case, mass protests broke out and the military stepped in to take over. However, an Islamist government in Sudan this time would have backing by Turkey and Qatar. A Muslim Brotherhood-aligned government in Khartoum backed by Turkish military strength and Qatari money would make full use of its Nile water allocation and support Ethiopia’s startup of the now-completed Renaissance Dam. Sisi cannot and will not let that happen. The Egyptian Army is the biggest gun in the arsenal of Sunni ground forces. If the Egyptian Army is busy in Sudan, then the Saudi/UAE condominium will lose access to troops from both countries.

The Blue Peoples

Since the 1960s, the Arab-led government in Khartoum has been trying to create factions of “Arabs” and “Africans”. Mixing over the centuries has made the groups visually indistinguishable, which gave rise to the Sudanese tradition of referring to black Africans as “blue”. But, despite their visual similarities, the Arabs of northern Sudan and the Africans of southern Sudan are separated by a wide cultural divide. The civil war between the north and south has been raging since the 1980s but the seeds of the conflict go back to the fifth century.

In the fifth century, Emperor Justinian of the Byzantines sought to enlist allies against Persia by converting the Nubians of the upper Nile Valley to Christianity. Nubian leadership seized the opportunity by converting immediately and, over time, Christianity spread down to the people. By the sixth century, southern Sudan was controlled by three Christian Nubian kingdoms: Makuria, Nobatia and Alodia. Makuria, the most powerful of the three, became a close ally of the Byzantines

In 639AD, Muslim Arabs conquered Egypt and invaded Nubia two years later. The Makurians fought them off, one of the few places able to hold off the Arab expansion. The “Baqt” trade agreement ended the conflict and represented a tenuous peace, one that lasted for over 600 years. The Arab forces were able to conquer the eastern side of the Nile and convert the local peoples there.

The Afro-Byzantine culture of the Nubians had its golden age from 750AD until the twelfth century when Saladin overthrew the Shiite rulers of Egypt who had been allies with Makuria. By the fourteenth century, plague and falling revenues from taxing trade along the Nile brought the Nubian kingdoms to their knees. Makuria , last of the three kingdoms, fell to invading Muslim from the east in the 1400s. When Makuria fell, Arab migration into Sudan began. The Nubians were Islamized and assigned to Arab tribes, but never became Arabized.

Circumstances creating a population divide between the north and south of Sudan have occurred repeatedly through history. The Funj Sultanate, which replaced the Christian kingdoms, had a nominally Islamic culture but retained many Nubian traditions. The sultanate covered Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. After the Ottomans destroyed the Funj, Sudan became an ungoverned area.

Britain entered the pages of Sudanese history in 1882 when the King of Egypt appealed to Britain for help putting down a rebellion of Egyptian and Sudanese nationalists. Britain intervened and Egypt became its de facto protectorate. Britain also repaid Egypt’s massive loans for a controlling interest in the Suez Canal.

After defeating Islamic zealots in southern Sudan in 1898, the British and Egyptians shared control of Sudan. Egypt’s independence in 1922 led to direct British control of Sudan and, from 1924 onward, Sudan was governed as two separate regions. The British divided Sudan into an Arabic-speaking Muslim north, and a Christian and Animist south where British missionaries could do their work. The missionaries were shocked to meet Sudanese tribes that called themselves “Christian” but knew little or nothing about the faith. These tribes were the last traces of Justinian’s efforts.

Christians and Animists in southern Sudan were disappointed in 1947 when it was decided that Sudan would gain independence as one country instead of two. Since independence in 1956, Sudan has been stuck in a cycle of military coups, rising food prices and revolutions.

Colonel (later General, self-declared) Omar al-Bashir became President of Sudan in 1989 when he led a group of young Islamist officers to overthrow the democratically elected government. The Islamists objected to the peace treaty the government had recently signed with the southern rebels and sought to implement Sharia law. Bashir’s regime represented a marriage of Islamism and Militarism and for nearly thirty years he brutally maintained stability.

Bashir’s downfall began in August 2018 when he announced that he would run for president again, contrary to his prior statements. Protests broke out in December 2018 when the regime ran out of money for subsidies and the Bashir regime was forced to triple the price of bread. By April 2019 protests had and intensified to the point where Bashir’s time was clearly up. Instead of allowing a popular uprising to occur, the military establishment forced Bashir to resign and formed the Transitional Military Council (“TMC”).

Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss

A process of shuffling the “front man” for the TMC then began. The Head of Intelligence and the Defense Minister each got a turn as Head of State for a few days. Eventually, the TMC found someone who had not been indicted by the ICC and who nobody in the West had ever heard of, Gen. Abdel al-Burhan . Burhan served as the third most-senior officer of the Sudanese Army and commanded troops in Yemen. The military establishment saved itself by moving its war criminals off-stage, but none of those people – including Bashir – will ever face consequences for their actions. Indeed, the TMC cannot dispose of Bashir because he is the only person with full knowledge of the patronage network he constructed during his 29 years in power. Without that patronage network, Sudan’s inefficient petrodollar economy cannot function.

The TMC’s deputy commander is Gen. Mohamed “Hemedti” Dagalo, commander of the vicious Janjaweed. His effective populist leadership and his ease with committing atrocities brought Hemedti into Bashir’s personal circle. In 2005, a portion of the Janjaweed mutinied when Bashir signed a peace treaty with the southern rebels. Hemedti’s loyalist forces defeated the mutineers and he was rewarded with a promotion to general and ownership of gold mines his forces had captured. In 2016, Bashir put Hemedti in charge of Sudan’s forces in Yemen and promoted him to Lieutenant General. The Janjaweed forces number 50,000 spread between Sudan and Yemen. Burhan provides the friendly face of the TMC and Hemedti provides the dagger from behind.

The Saudis and the UAE are afraid of another round of “Arab Spring” uprisings leading to more Islamist governments. When Bashir’s regime began to crumble Saudi/UAE offered to prop up the regime in exchange for turning away from Turkey/Qatar and repressing the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan. Once it became clear Bashir’s time was up, the Saudis/UAE declared support for the TMC. The TMC very publicly displayed their loyalty to the Saudis by refusing to accept diplomats from Qatar and arresting prominent Muslim Brotherhood members.

In a sign of where their priorities lay, Burhan’s first foreign tour as head of the TMC went to UAE and Egypt while Hemedti’s was to visit the Saudis. Hemedti’s control of the Janjaweed militia made him the preferred candidate for the Saudis. The Saudis cannot allow Sudanese troops to be pulled out of Yemen.

Peace is far from guaranteed in Sudan because the TMC currently faces two parallel negotiations that are difficult, maybe impossible, to square. First, the state security forces and militias are negotiating a security pact. Khartoum and the major cities are controlled by the military, but the countryside has been carved into about a dozen fiefdoms by various paramilitary groups, including the Janjaweed.

The second negotiation is with the civilian leaders of the revolution for a transition of power. The goal of the TMC is to give enough power up to keep the international community happy, but not enough for the civilians to be able to defy the military. None of the armed opposition groups have joined the civilian revolutionary council, which means the people with guns (i.e. the ones that matter) have not decided the war is over.

The South Sudan Trap

The path taken in the Horn of Africa and the wider Middle East will depend very heavily on the outcome in South Sudan. Many lives and much prosperity hang on the stability of a country that has only existed for eight years and has been embroiled in civil war for five of those years. South Sudan has taken on global importance because it holds the oilfields that are the lifeblood of Sudan’s petrodollar economy. Without the flow of oil revenues, Sudan’s government cannot function, and troops will likely be pulled out of Yemen to control chaos at home. The September 2018 peace treaty in South Sudan rests on power-sharing agreements among South Sudan’s various factions that the US State Department described as “not realistic or sustainable”.

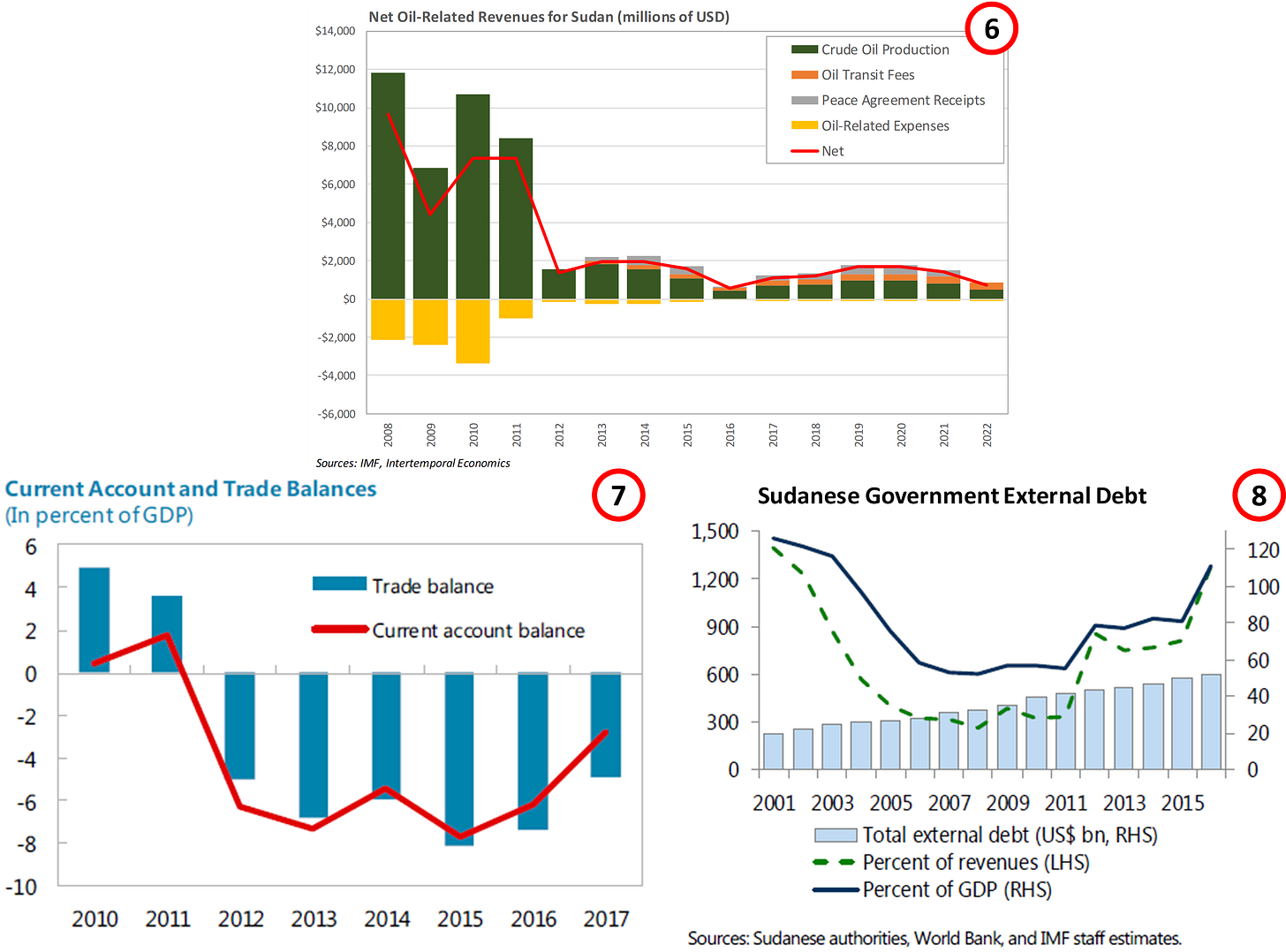

It is probable that the only reason Bashir’s regime lasted beyond South Sudan’s independence is the decade of residual payments that was agreed to. Once the residuals stop coming in 2022, Sudan will only receive pipeline tariffs on the oil that South Sudan actually produces (Chart 2). That “actually” is the key to South Sudan’s stability. War, population displacement and corruption have brought South Sudan’s oil production from over 400,000 barrels per day in 2010 down to 150,000 in 2019. South Sudan has experienced the largest mass exodus of refugees since the Rwanda genocide. One-third of the population has been displaced and the 80% of the population is in poverty. Unless significant investments in infrastructure, refugee aid and oil production are made, South Sudan’s oil output will fall at an accelerating rate (Chart 3).

Consider the situation from the point of view of the Sudanese military. When they ran the South Sudan, oil production was higher and the government in Khartoum got to keep the money (Charts 6, 7, 8). The oilfields are right across the border and the Sudanese military-security leaders know they have the technical and (with the help of rich friends) financial means to bring output back to pre-2011 levels. The choice the TMC faces: take the oil from a weak, divided, bankrupt South Sudan or face a massive restructuring of an inefficient economy and a conservative Muslim population unfriendly to banking. Water flows downhill and taking the oil is clearly the path of least resistance for a military-security regime. For a military regime backed by the Saudis and the UAE, could easily be perceived as the best choice from a list of bad choices. Of course, a civilian transitional government would not take such an action. But, given the horrible economic conditions in Sudan, I do not expect a civilian government to last long, if one is even formed at all.

If Sudan does take military action in South Sudan to seize the oil fields, there will likely also be a confrontation between Sudan and Uganda. These two countries have long competed for control over South Sudan. During the South Sudanese civil war, the current President Salva Kiir was reliant on Uganda for military aid. The US has become embroiled in the situation because weapons sent by the US to Uganda for fighting Al-Qaeda have been diverted to South Sudan’s military.

Conclusion

Although the media’s focus is on the confrontation between the US and Iran, I do not think either of those counties will be the first shot in open warfare. Of course, both sides have been and will continue to snipe at each other, but I think Trump’s calling off a retaliatory strike against Iran’s shooting down of a US spy drone was a “red line” moment. Trump showed his hand too early by coming up with a lame excuse (100-200 “people” killed) instead of threatening “fire and fury”. Trump does not want a war with Iran and will actively try to avoid it, but that does not mean he cannot be convinced that war with Iran the best of a list of bad options.

Investors should expect low-level tanker incidents to continue weekly with something blowing up once a month. The Iranians do not want to provoke a war, but they definitely want to limit Trump’s list of options. The US will not move a carrier through the Strait of Hormoz if there is any threat of an attack. For the US, as a maritime power, the carriers are too big to fail. Once the well-earned reputation of an undefeatable extension of power is broke, the carrier becomes a very vulnerable and very expensive target. Keeping a carrier out of the Persian Gulf limits the ability of the US to get between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

The only person that has reason to provoke a war now rather than later is Mohammed Bin Salman. The admitted Saudi breakeven price for Brent is $80, which means it is likely much higher. The Saudis are going to run out of cash at some point. More importantly, each day more Houthi missiles hit increasingly sensitive Saudi targets. The more successful the Houthis are at handicapping the Saudis, the more Iran will ship production and tactical expertise to allow them to build missiles for themselves. The Saudis cannot face an endless stream of missiles from their neighbor and it is clear the Houthis will not be defeated on their home turf – which is all they need to do. MBS will eventually be met with the reality that the least bad option is to try to cut the head off his crafty rival before he is killed by a thousand pin pricks from the south.

Even if we assume MBS is willing to fight it out in Yemen and take the missile strikes, he cannot do it with domestic ground forces. That is why the governance of Sudan is of vital importance to the Saudis. Without a steady stream of soldiers of fortune, the Saudi presence in Yemen will fold immediately. The Saudis will do everything they can to keep the military-security apparatus in Sudan from losing power. If the civilian government gains power or a period of chaos takes place in Sudan the strategic situation of the Saudis will be dire.

In the past Saudi monarchs could count on nearly unconditional US support on issues related to Iran. However, a Trump win in the 2020 election means there will be no impediment to increasing US oil production. Currently, the major capacity restraint is pipelines, which can be constructed easily and cheaply. The expensive parts of the pipeline business are in the regulatory and lobbying space. Clearly, the Trump Administration would not shy away from a production goal of twice the size of Saudi Arabia or Russia. The potential for policy wins on energy, national security, and the trade deficit could make walking away from the Saudis appear as an the most attractive option to the Trump Administration. The outcome would be a major expansion of the Brent-WTI spread.

Once the uncertainty of US backing becomes clear to MBS, if it has not already, he will realize that a countdown to survival for him personally has begun. The Crown Prince can be replaced and offered as a sacrifice for peace, literally. If he wants to become King of Saudi Arabia, which is his best chance of living to forty, he must provoke a war between the US and Iran before his time is up. Desperate men who think they are the smartest ones in the room are a very dangerous thing.

Postscript

This note provides the opportunity to address a topic that has occupied my mind for most of 2019. That is, how quick human beings are to forgive their own sins, this writer included. The worse the sin the quicker forgiveness is granted.

It is easy to write off Hemedti and others like him as monsters. We look down our noses at him, but his atrocities are committed on our behalf. Hemedti only does what he does because of the world's insatiable demand for gold and rare earth elements to make our electronics work. We all bear responsibility for his sins. Indeed, even more so because we choose to avert our eyes. To Hemedti’s credit, he has no illusions about the game being played.

Of course, the atrocities committed to acquire the mines are not the last. The only source of cobalt in the world is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Twenty to forty percent of the mine workers are children under 12 using hand tools. Children are preferred because they can get into small tunnels and are unable to rebel against the oligarchs that own the mines.

The next time you pick up your phone take a second to think about the children who suffered and died to put it in your hands. Indeed, pound for pound Elon Musk with all his batteries is high in the running for worst abuser of children in the history of the world. But it's no matter because he designs cool cars and is saving the planet, or the species, or whatever. And when you make a call, listen for the voices of those children. You will hear them, if you have the ears to. Ring Ring.

If you enjoyed reading this post, please do me the favor of sharing it with someone else, or clicking the ‘Like’ button below. Both are free and easy ways you can help further my goal of teaching people non-statistical economics and spreading skepticism of “greenwashers” such as Elon Musk.