· Extrapolating the pre-COVID trend for labor force growth, the labor force is currently 5 million workers short of where it should be.

· Prices will continue rising until real wages have fallen to an appropriate level for the productivity of the labor force.

· Bottom Line: The FOMC will likely grab onto the upcoming easing of price growth to justify a pause in rate hikes. Perhaps they will back up their words with action, but it will take more than “big bazookas” in September to convince this writer otherwise.

Thank you to everyone who has taken the time to hit the like button, comment, or subscribed. If you enjoy this note, please take a moment to like, comment, and subscribe as each of those actions puts a little “gas” in the tank here at Intertemporal Economics. Just clicking like is immensely helpful and is an important source of emotional compensation for writing these notes. Even better is to share The Trader’s Brief with a friend!

Another “strong” employment report for August locked in expectations for a 75-bps increase to the policy rate at the next FOMC meeting. Such an outcome does seem likely at this point, but it means the Fed is running out of room to raise the policy rate without inverting the yield curve. Indications about the economy coming out of the labor market are all over the place. The structural change in the labor market is masking some, but not all, of the cyclical indicators economists typically use. This note is about the health of the labor market and exploring the implications for inflation.

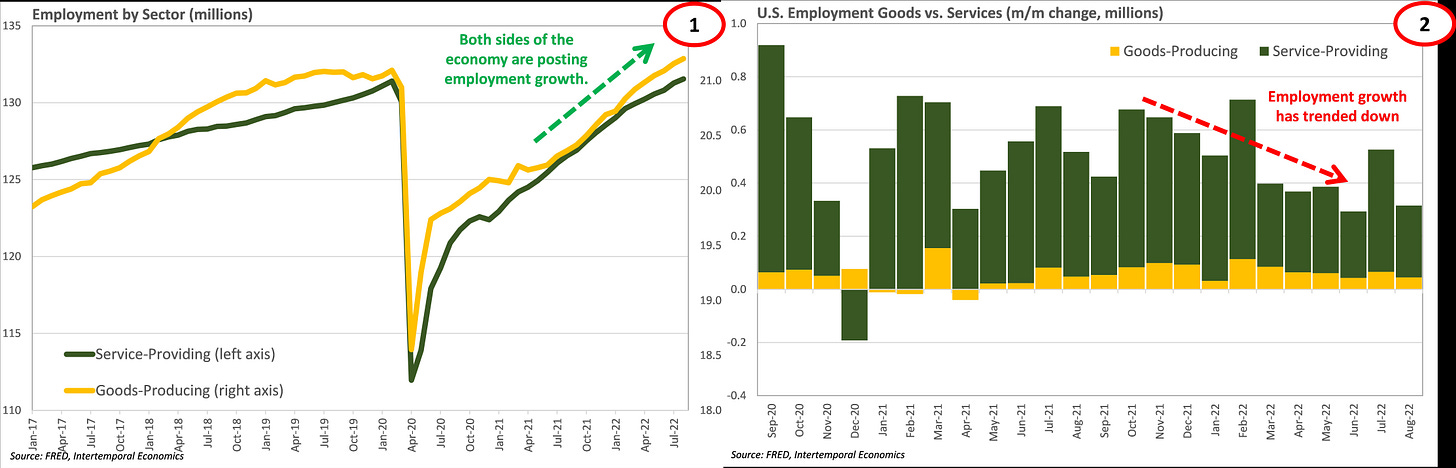

The first example of conflicting indicators comes from aggregate employment versus monthly change. Aggregate employment on both sides of the economy continues to grow and goods-producing industries have surpassed their pre-COVID employment level (Chart 1). However, employment growth has trended down despite aggregate employment being far behind its pre-COVID trend. If anything, all else equal, employment growth should have accelerated in the second half of 2021.

The reason employment growth has slowed is that the labor market has rapidly reached the level of tightness seen pre-COVID (Chart 3). A quick recovery to pre-COVID tightness would normally be a good thing but that is not the case in 2022 because the labor force remains smaller than 2019 in absolute terms (Chart 4). Extrapolating the pre-COVID trend for labor force growth, the labor force is currently 5 million workers short of where it should be.

Structural Shifts

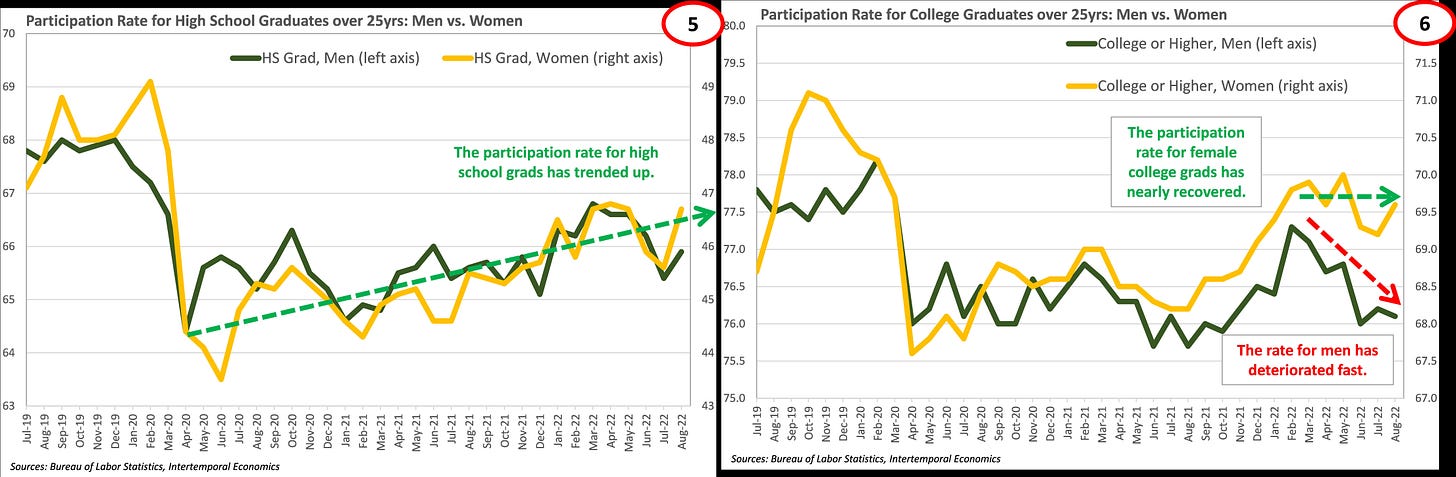

Clearly the U.S. labor market is dogged by a participation problem. Nobody wants to work. The good news is that the participation rate for high school graduates without a college degree continues to trend up (Chart 5). That being said, participation for this group remains 1.5 percentage points below 2019 rates.

Unfortunately, developments in participation for college graduates are nothing but bad (Chart 6). For men, participation is 1.5 percentage points short of pre-COVID levels and is trending down. The participation rate for female college graduates is also 1.5 percentage points below its pre-COVID peak but stable.

The U.S. labor has a very bad mismatch between worker education and vocational needs. Just like the bubble in residential capital investment, the U.S. Federal government created a bubble in human capital investment via subsidized loans. The result is that despite rising participation rates, the number of workers with only a high school diploma is falling (Chart 7). In contrast, the number of workers with a college degree or better continues to rise rapidly (Chart 8).

The net result of the above is that the employment-population ratio for women is rising but is falling for men (Chart 9). Across levels of education employment-population ratios topping off (Chart 10). The labor market has fewer workers than in 2019 to support national output but with a rising population.

The Labor Market-Price Nexus

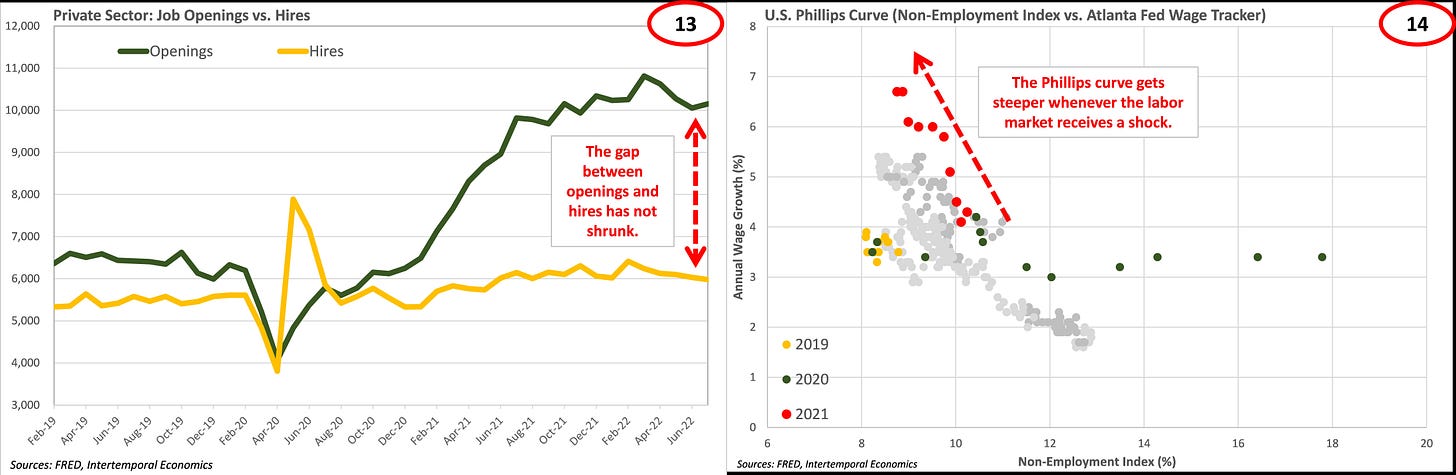

The reason economists pay so much attention to the labor market is, of course, because it adds a momentum effect to inflation. Wages are among the stickiest prices in the economy, which means that structural changes take so long to play out that they become “normal”. The business sector needs to coax more workers into the labor force, and it will not be cheap. The most visible sign that there is a labor shortage comes from the Beveridge curve (Chart 11). This writer recently published a note recently on whether the Beveridge curve has shifted. In short, this writer does not think the curve has shifted but that the demand for labor is strong and broad resulting in an unusual bottleneck. However, as employers give up on searching for new hires because the effort is not worthwhile the cost of searching will fall. That process appears to be playing out (Chart 12). The result will (hopefully) be that demand for labor becomes more cyclical and shifts across industries as the business cycle progressive for now. For now, the demand for labor comes from every industry, all at the same time. The result is a bottleneck in hiring that drives up wages as employers fight at the bottleneck for the available supply.

Search costs have come down, which has kept the number of job openings high. However, the hiring rate remains stubbornly low as employers cannot find qualified applicants (Chart 13). The upshot of this is that the labor market suffered a sudden shock and the Phillips curve suddenly steepened (Chart 14). Policymakers had been so sanguine about the shift in the data being permanent, but their mistake was forgetting that the principals of economics do not change. Two sets of data might look different, but if they are part of the same process then they are simply different states within a larger set of possibilities. That is what the statistical economists miss.

The Price of Labor

With very little “inventory” of labor available the pricing curve becomes very steep, possibly vertical. That is the case for any and all non-substitutable goods and services. The flip side of that reality is that the growth rate for prices will fall rapidly once demand wanes or supply grows. Market conditions currently favor very high wage growth, but conditions are right for a complete flip to slow or even negative wage growth (Chart 15). One of the best indicators that conditions have flipped will be a slowdown in wage growth for the youngest workers, aged 16-24yrs, who exhibit highly pro-cyclical wage growth (Chart 16). Another sign will be that a gap between wage growth for full-time and part-time employees returns (Chart 17). The current parity in growth rates is highly unusual.

One sign of labor market supply imbalance is that low skill workers are experiencing the fastest wage growth. The US education system stopped producing them and the immigration system keeps them out, so the result is shrinking supply and growing demand (Chart 18). The charts below show the market resolving government-generated supply imbalances via prices.

Put Me In Coach

Unfortunately, the prospects for a large-scale return of nonparticipants looks bleak. The percentage of nonparticipants who want a job is nearly back to pre-COVID levels, but the number of nonparticipants is five million higher than it was in 2019 (Charts 19 & 20). That is an imbalance that will time and price adjustments to resolve. Therein lay the seeds of an inflationary cycle as expectations change over time.

Conclusion

The U.S. labor market was severely distorted by the federal government’s response to COVID with the net result being five million workers leaving the labor force. With a shriveled labor force and demand boosted by government payments the result has been rising nominal wages and falling real wages. Prices will continue rising until real wages have fallen to an appropriate level for the productivity of the labor force. Because wages are arguably the stickiest price in the economy that adjustment process will likely take some time, if for no other reason than the scale of adjustment needed.

Therein lies the danger that the Fed fears so much, a change in expectations to a high inflation regime. Under such a regime a wage-price spiral can develop because everyone is expecting prices to move higher and soon so they begin to include expected inflation in their prices and revise prices more often. It is hard to see how this inflationary process can be broken without a severe recession. However, no political or monetary policymaker wants to be the one blamed for pulling the recession “lever”. The FOMC will likely grab onto the upcoming easing of price growth to justify a pause in rate hikes. Perhaps they will back up their words with action, but it will take more than “big bazookas” in September to convince this writer otherwise.

Related Notes

“U.S. Labor Market: The Fed’s Participation Dilemma” of 9 June 2022

“The Underpinnings of a Nonlinear Phillips Curve” of 25 September 2018

“The Beveridge Curve and the Magic of the Movies” of 9 August 2022

One of the best overviews of the US labor situation I have ever read! Thanks for this excellent post.

Runs out of room before inverting what yield curve? Isn’t the yield curve already inverted?